LARNet; The

Cyber Journal of Applied Leisure and Recreation Research

Role of Manager and Visitor Self-Interest in Wilderness Management:

Nordhouse Dunes and Limits of Acceptable Change

(September 2003)

Dennis B. Propst, Dept. of Park, Recreation & Tourism Resources,

Michigan State University

Maureen H. McDonough, Dept. of Forestry Michigan State University

Ami Wiita, Dept. of Natural Resources, State of Alaska

Contact: Dr. Dennis B. Propst,

131 Natural Resources Bldg.,

Michigan State University,

East Lansing MI 48824-1222

phone 517/353-5190, X119; fax 517/432-3597;

email: propst@msu.edu

ABSTRACT: The traditional role of the resource manager as

omniscient,

autocratic expert is being challenged in conjunction with challenges to

authority-based leadership models across society. This trend

poses

a dilemma for the managers of eastern wilderness. Some form of

recreational

use restriction may need to be applied to these small preserves in the

populous East, but citizens and wilderness users increasingly demand a

say in such decisions. Study objectives were to develop a conceptual

model

that integrates the motivator, self-interest, into the "Limits of

Acceptable

Change" planning system (LAC) and to illustrate how to use the model to

resolve manager/user conflicts. A yearlong survey of visitors at

Nordhouse

Dunes Wilderness (Michigan) provided a case to which to apply the

model.

Survey results presented managers with conflicting information about

managers’

predetermined management strategies. A key finding was that

managers

and users differ in perceptions of crowding and appropriate behaviors

at

Nordhouse Dunes. Once researchers discussed the survey results with

managers,

assisted in the discovery of areas of mutual self-interest and

facilitated

a cooperative learning session, managers incorporated conflicting

information

into their decisions and changed preconceived management actions. The

mutual

self-interest model holds much promise for conflict resolution—before

the

conflicts begin.

KEYWORDS: outdoor

recreation, wilderness, self-interest, common

property resource management, limits of acceptable change, conflict

resolution

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The authors wish to thank the U.S. Forest

Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station (Chicago, IL) for the

funding that sponsored this research. We also express our appreciation

to Nordhouse Dunes Wilderness managers, John Hojonowski and Ramona

Venegas-DeGeorgio,

for their hospitality and assistance in planning and implementing the

study

and communicating the results to others. The views and conclusions

expressed

are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the U.S. Forest

Service

or its employees.

Introduction

Garrett Hardin, in his classic treatise on natural

resource depletion, argues that the tragedy of the commons in

wilderness,

parks, and other reserves leads to increased visitor impacts and hence

steady erosion in the values that visitors seek (Hardin,

1968).

Burgeoning populations coupled with trends such as urban expansion and

greater mobility present threats to all resources. Policies and

new

cultural norms that limit the absolute numbers of humans and their

impacts

are mandatory (Hardin & Baden, 1977; Keyfitz, 1989; Hardin, 1993;

Miller,

1996) else “freedom in the commons brings ruin to all” (Hardin, 1968,

p.

1244). Carrying the commons argument further implies that

unrestricted

access to wilderness, parks and other reserves will inevitably lead to

these protected areas being “loved to death” since, as Hardin implies,

humans are incapable of limiting individual consumption of

common-property

resources for some greater collective good.

Though criticized as suffering from cultural myopia

(Feeny, Burkes, McCay, & Acheson, 1990; Shepherd, 1988), Hardin’s

work

has led some natural resource scientists and managers to resist calls

for

management approaches involving collaboration with publics. Hardin

concluded

that one way to avoid the tragedy was through government control

(Hardin,

1968; Hardin & Baden, 1977). Namely, state institutions

through

the professionals they employ (e.g., resource managers) should regulate

uses and users. These arguments have been used to support a

continuation

of the conventional authority-based model of "leadership" (Heifitz

&

Sinder, 1988). Yet, one often overlooked qualification that

Hardin

made is that, to be effective, any type of social arrangement such as

restricting

visitation should be “mutual coercion, mutually agreed upon by the

majority

of the people affected” (Hardin, 1968, p. 1247). Mutual coercion

is consistent with Leopold’s land ethic, which calls for interdependent

individuals or groups to develop means of cooperation in order to

impose

limits on the human use of natural resources (Leopold, 1966, p. 238).

Hardin’s qualification poses an interesting dilemma

for the management of America’s eastern wilderness areas.

Some

form of recreational use restriction may need to be applied to these

relatively

small preserves in the populous East, but we live in an age and society

in which members of the public increasingly demand a say in government

decisions that affect their use of a resource (Feeny et al., 1990;

Propst,

Wellman, Campa, & McDonough, 2000; Tipple & Wellman 1989;

Wellman

& Tipple 1990; Wondolleck, 1988). The trend toward

decentralization,

greater user participation in resource management, “co-management”, and

“participatory management” reflect dissatisfaction with top-down,

autocratic

and bureaucratic models (McCay & Jentoft, 1996).

Furthermore,

there is evidence that individuals who lack knowledge of technical

scientific

issues can quickly learn about their critical features and choose

policy

options similar to those chosen by scientists (Doble & Richardson,

1992; Ferguson, 1987) or are at least as likely to ask the right

questions

and find novel solutions (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1983). The traditional

role

of the resource manager as omniscient, autocratic expert is being

challenged

in conjunction with challenges to authority-based leadership models

across

society (Heifitz & Sinder, 1988; Sirmon, 1993; Brick, Snow & de

Wetering, 2001).

Several bodies of literature converge on a common

conclusion: experts possess a belief system that often conflicts with

the

belief systems of the people who they are trying to serve. In the

outdoor recreation literature, Manning (1999) summarizes numerous

published

studies indicating that professional outdoor recreation manager

perceptions

of problems and their solutions often differ markedly from those of

visitors.

Similar findings have been observed in the health care profession

(Ferguson,

1987), the park and landscape design field (Clare Cooper Marcus, 1990;

Halpirn & Burns, 1974; Hester, 1984; Hultsman, Cottrell, &

Zale-Hultsman,

1987; Whyte, 1980), business (Peters & Waterman, 1982),

environmental

planning (DeYoung & Kaplan, 1988) and urban forestry (Magill,

1988).

Attempts to institutionalize the knowledge of expert/nonexpert

differences into professional natural resource management training are

as scarce as some of our natural resources (Wellman & Tipple, 1992;

Propst et al., 2000). The philosophical and ethical beginning

points

for such training exists in the natural resource and environmental

policy

literature (Shannon, 1991; Wellman & Tipple, 1990, 1993).

Shannon

argues for the need for professional resource managers to build trust

with

citizens by engaging in ongoing “civic conversation”.

Wellman

and Tipple (1990) argue for “direct democracy” where, instead of

deference

to the traditional role of the expert, recreation managers (in this

case)

should encourage active participation and hence contribute to the

growth

or perhaps rebirth of democracy. Hefitz and Sinder (1988), who

argue

that in a democracy real leadership means turning the work of the

community

back to the community, support their position1

.

One way to implement the Heifitz and Sinder “communities

of interest” approach to natural resource management is suggested in a

report for the Forest Policy Center of the former American Forestry

Association

(Wellman & Tipple, 1992). In this report, Wellman and

Tipple

challenge professionals to become managers of participation as well as

managers of resources. Managers of participation develop active

citizens

who, in turn, frame alternatives and assist in cooperatively managing

natural

resources. Citing scholarly efforts at redefining the

relationship

between public administrators and the citizens they serve (Reich, 1988;

Wamsley, 1990), Wellman & Tipple (1992) offer some practical

guidelines

for developing constructive partnerships between communities and

organizations.

In addition, Wellman and Tipple (1990) and Propst et al. (2000) offer

several

ways in which education can change the worldview of the resource

manager

from traditional autocrat (passive citizenry mode) to facilitator of

public

interest and responsibility (active citizenry mode). Knight and

Landres

(1998), Clark, Willard and Cromley (2000) and Brick et al. (2001)

provide

case studies of successes and failures in “collaborative conservation”,

or the attempt to bring together a diverse coalition of interests to

manage

natural resources by voluntary consent and compliance rather than

enforcement

by legal and regulatory coercion.

Our purpose is to extend such recommendations for

institutional and educational reform into a specific public policy

arena.

We start modestly by arguing for the need to integrate the motivator,

self-interest,

into the “Limits of Acceptable Change” management framework as applied

to eastern wilderness in the U.S. Building upon the knowledge

that

resource managers’ worldviews often differ substantially from those of

the people they serve and adding contributions from psychology and

political

science, we make recommendations regarding (a) a self-interest approach

to the management of the Nordhouse Dunes Wilderness, (b) the role of

“mutual

self-interest” in forging effective partnerships in resource

management,

and (c) how the professional resource manager can implement and fulfill

the challenges of this new role in a society where citizens demand

changes

in the way the expert goes about his/her business.

Literature Review

Researchers have known about the disparity in expert

versus client views of the world for over 25 years (Manning,

1999).

Yet altering the way resource managers interact with publics has not

been

a foregone consequence of such knowledge. Why not? The

cognitive

psychology literature on human decisionmaking provides a useful

beginning

for understanding this question.

One approach to understanding the mechanisms by which

humans learn, make decisions and act upon their decisions is the

limited

capacity/cognitive map model of human behavior (Downs & Stea, 1973;

Kaplan & Kaplan, 1983; Kaplan & Petersen, 1993). Humans

cannot

think about all of their stored knowledge at once. In other

words,

there is “a limit to how much activity the cognitive system can support

at a time” (Kaplan & Petersen, 1993: 46). Familiarity with a class

of stimuli and appropriate responses is helpful to organisms with

limited

capacity to process the amount and complexity of information with which

they are constantly bombarded. We can act quickly and

appropriately

with a minimum of storage capacity utilized, thereby freeing up

additional

capacity to process environmental information with which we have little

familiarity and experience.

The cognitive map model of human brain functioning

has widespread support (Lynch, 1960; Downs & Stea, 1973; Kaplan

&

Kaplan, 1983; Kotulak, 1996). One implication relevant to this

discussion

is the potential bias towards making decisions quickly and with limited

information rather than optimally or rationally. Such a

bias

is supported by evidence concerning how managers and other

professionals

actually make decisions. Namely, when faced with complicated

decisions,

professional often “muddle through” (Lindblom, 1979) or “grope their

way

along” (Behn, 1987; Peters & Waterman, 1982).

Furthermore, human cognition is said to be “conservative”

in the sense that, once dense associations of familiar representations

and their successful responses have been formed, there is great

reluctance

on the part of the organism to alter his or her cognitive map--hence

the

all too familiar resistant response to change, “but we’ve always done

it

this way before” (Kaplan, Kaplan, and Ryan, 1998).

Herein lies the cost of this limited capacity/cognitive

map/quick response system that has evolved over the millennia.

Experts

within any profession, including natural resource management, because

of

their training and experience, become familiar with various classes of

technical, scientific information as well as a range of responses as to

what to do when presented with such information. This potentially

limited range of responses is resistant to change not only because of

the

cognitive maps that have formed over time but also because of the

motivational

coding of values that goes along those maps (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1983;

Gilovich, 1991). Thus, experts possess a powerful cognitive and

emotional

self-interest

in the actions and decisions that stem from their professional

knowledge

and experience. This cognitive self-interest is bolstered by the

shared values and purposes inherent in professional groups (e.g.

foresters,

wilderness managers, park rangers) (Orren, 1988). Indeed,

organizations

such as the U.S. Forest Service work very hard to develop and maintain

these shared values in their employees (Bullis & Tompkins, 1989).

Perloff (1987), in his review of psychological, economic

and evolutionary literature pertaining to human behavior, argues that

the

variable of self-interest is a powerful and effective force underlying

our actions. Perloff argues that despite its malignment as

antithetical to community goals, self-interest is central to American

character,

contributes positively to personal well-being, and hence is supportive

of the public good. Furthermore, social support (in the

form

of welfare provided by the state) often works against

self-interest.

Giving advice and assistance, no matter how well-intentioned, may be

excessive,

untimely and inappropriate thereby creating unnecessary dependencies

that

limit self-help and initiative (Perloff, 1987). In the

political

science literature, the same argument is made by Heifitz and Sinder

(1988)

when they propose that when leaders act as authorities who can solve

problems,

citizens no longer feel any personal responsibility for the problem or

its solution. In a similar vein, Perloff qualifies the definition of

self-interest

by linking it to personal responsibility, noting that in the case of

cancer

patients, for example, self-interest leading to personal responsibility

for one’s health leads to more effective coping strategies than the

passive

acceptance of the inevitability of the disease. Perloff

concludes

his review by stating that self-interest enhances performance (a strong

motivator), conserves one’s resources, and helps cope with illness and

traumatic life events. Less self-interest leads to lowered

feelings

of personal responsibility.

The Limits of Acceptable Change (LAC) planning process

is one attempt to infuse public self-interest into the management of

wilderness

areas (Stankey, Cole, Lucas, Petersen, and Frissell, 1985; Stankey,

1999;

Slover, 1996). LAC and similar frameworks are even being

integrated

into the guiding principles and operational policies of entire national

park systems (Graefe, 1996; Manning, 1999). However fortified

wilderness

managers may be with policy or visitor data regarding the acceptability

of various management practices, they are still left with the nagging

question

of how far to go in applying the LAC results versus their own

expertise.

How should social data be integrated with the trend toward

participatory

management? What should be done when visitor and manager views of

what constitutes acceptable change are not the same?

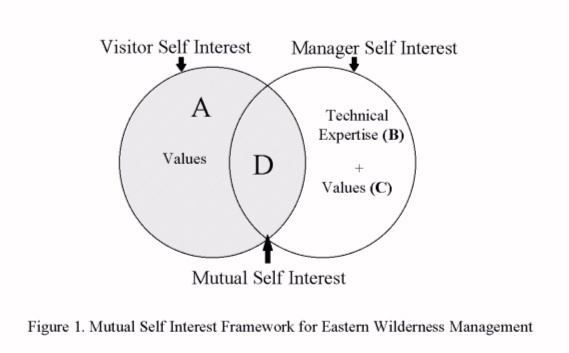

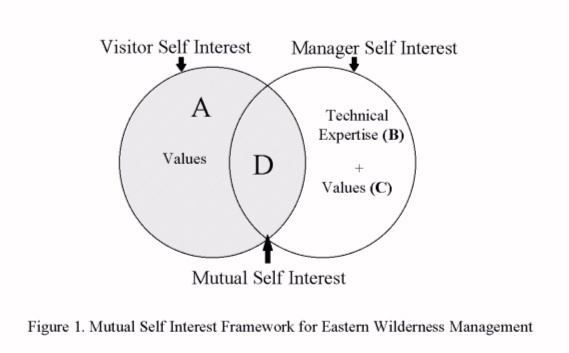

Manager self-interest can be separated into technical

expertise (learned through training) and values and beliefs regarding

wilderness

(some of which attract people to the profession and some of which are

learned

as members of the profession). Part of the challenge to answering

the two questions posed above is that it is cognitively difficult for

managers

to separate their technical expertise from their own values and beliefs

(Figure 1).

Thus, manager self-interest is used to make decisions

that seem rational to them, but not to the visitors they are attempting

to serve. Since wilderness is a social construction, the

contention

of management that its role is to maintain “purity” is clearly

one-sided

and even delusional (Cronon, 1995). Managers often either

assume

no visitor self-interest or that visitor self-interest conflicts with

management-defined

purity standards. In addition, managers may not see how the

application

of their technical expertise is colored by their values. In

short,

managers often presume that visitors cannot sustainably manage the

commons.

Indeed, the typical reaction is to dismiss user input that does not

agree

with manager views. Building upon Perloff’s synthesis and

Hardin’s

“mutual coercion” qualification regarding the commons, the framework

adopted

in this paper (Figure 1) calls for a balance of visitor self-interest

(i.e.,

what visitors value and help themselves to achieve) and manager

self-interest

(i.e., social support as defined and provided by management). In

natural resource management, social support would include the provision

of services and facilities for visitors’ convenience based on managers’

perceptions of what is best for the visitor. The implication is

that

by leaving visitors out of the decisionmaking context, managers may

inadvertently

create unnecessary dependencies and visitor expectations of not being

involved

in natural resource management in a way that Leopold called for in his

land ethic. Consistent with Figure 1, we interpret mutual

coercion

to mean, “behavioral restrictions mutually agreed upon by all groups

affected,”

in this case by management decisions. The advantage of this framework

is

that efforts to limit resource use may not seem coercive in a negative

sense (cf. DeYoung & Kaplan, 1988) once points of mutual

self-interest

are identified.

The Case Of Nordhouse Dunes

A study at Nordhouse Dunes Wilderness Area (NDWA)

in Michigan provides a case to which the mutual self-interest model may

be applied. Nordhouse Dunes is the only designated wilderness

area

in Michigan’s Lower Peninsula. It is within a six-hour drive of

roughly

14 million people, including the cities of Chicago (IL) and Detroit,

Ann

Arbor, Lansing, Flint, Saginaw and Grand Rapids (MI). This wilderness

area,

designated in 1987 primarily because of its unique dunal ecosystem and

endangered flora and fauna, consists of only 3,450 acres. The western

border

of the wilderness consists of 7,300 feet of undeveloped Lake Michigan

shoreline.

Located within the Huron-Manistee National Forest, the wilderness

shares

its eastern border with the Nordhouse semiprimitive motorized area and

its western border with the Lake Michigan Recreation Area, which

contains

a highly developed campground. The U.S.D.A. Forest Service

manages

all three areas. Ludington State Park borders the wilderness to the

south

and is managed by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

The location of Nordhouse Dunes creates multiple

management questions for the wilderness. These include use pressure,

undesignated

main entry points into the wilderness from surrounding recreation

areas,

and impacts of surrounding developed recreation areas, which differ in

purpose from the wilderness, on wilderness use. Also, prior to

its

wilderness designation, there were traditional/historical uses of the

area

such as off-road vehicles and snowmobiling. Forest Service

managers

expressed concern that these uses, which were incompatible with a

wilderness

designation, were continuing to occur in the area.

To cope with these management challenges, staff of

the Huron-Manistee National Forest began to develop a Limits of

Acceptable

Change (LAC) management plan. To help develop the plan, the U.S.

Forest Service contracted with researchers at Michigan State University

to supply the necessary visitor information. The purpose of the visitor

study was to estimate visitation to the wilderness area and describe

its

users and their perceptions of and preferences for the NDWA. A

full

analysis of all data collected in this study can be found in McDonough,

Propst and Wiita (1995) and Wiita (1998).

Methods

A combination of stratified and random sampling

procedures was employed in the visitor study. Sampling was

conducted

from May 1993 to March 1994. The desired sample size was

based

on Forest Service estimates of 15,000 to 20,000 visitors per

year.

A sample size of 3% was used to set a goal of collecting 500 to 700

surveys

over the life of the project.

The sampling methodology was structured to obtain

a representative sample of wilderness users across all times of day,

days

of the week, entry points and times of the year. Seven main entry

points

into the wilderness were identified and sampled. Because of lower

visitation

and a reduction in the number of available interviewers, sampling

frequency

decreased during the fall and winter sampling periods. With the

exception

of winter, all possible time blocks during daylight hours were selected

to assure representatives across days of the week and entry

points.

The result was a sampling design, which was representative of all

possible

daylight time periods and access points from May to March.

Interviews were conducted on site to reduce costs,

increase response rates, counteract recall bias and obtain valid

estimates

of use. Each person in a party over the age of 15 exiting the

wilderness

for the day was interviewed to gather the necessary limits of

acceptable

change information. Interviewing only those groups who were

exiting

for the day minimized the double-counting that would occur if both

entering

and exiting parties were interviewed.

Data collection instruments used in other Eastern

wilderness areas were provided by Dr. Alan Watson (Wilderness

Management

Unit, Forest Sciences Lab, Missoula, Montana). Most questions for

the instrument in this study were taken directly from these instruments

to enable the direct comparison of these results to those of other

wilderness

studies. The instrument contained questions focusing on visitor group

characteristics,

trip and wilderness visitation characteristics, wilderness activities,

visitor perceptions and expectations, level of acceptable encounters,

crowding

norms and visitor demographics.

Interviewers contacted 772 visitors. A total

of 506 visitors constituting 285 groups were interviewed. The

response

rate for the study was 75% as 166 people refused.

Managers’ perspectives were assessed from a variety

of sources throughout the study. Specifically, manager views were based

on qualitative data generated through content analysis of recorded

notes

from a lengthy planning meeting and verified with a variety of printed

materials. During the planning stages of the research design,

researchers

and Nordhouse managers met to agree upon research objectives and

content

of the survey instrument. A note taker kept a detailed written

record

of the meeting. As recommended by Henderson (1991) as a method of

increasing reliability (“dependability”) in qualitative data, the notes

from this meeting were independently evaluated by three separate

researchers

who then met to reach consensus regarding consistent themes.

These

themes were recorded and shared with the managers to check for

discrepancies.

This process created an “audit trail”, which could be checked for

consistency

by managers and other researchers (Henderson, 1991). As an added

check for consistency, researchers and managers reviewed newspaper

accounts

and internal planning and public involvement documents that had been

prepared

by Nordhouse staff. Participation by multiple researchers

and

agency representatives in sampling, data collection, coding, analysis,

and reporting was used to enhance the confirmability, or objectivity,

of

the qualitative findings (Henderson, 1991).

Manager Perceptions of Nordhouse Dunes

A consistent theme from the qualitative analysis

was that managers perceived Nordhouse Dunes Wilderness Area to be

overused

and overcrowded, especially along the Lake Michigan shoreline.

Quotes

from an article that appeared in the major newspaper of the state

capital

(Lansing) exemplify this theme:

"It's [Nordhouse] just overused. People are loving

it to death…They [visitors] don't find the solitude they're looking

for,

especially along Lake Michigan" (Ingells, 1991).

Use was estimated by managers to be approximately 15,000

- 20,000 visitors, figures exclusive of the significant number of users

the Forest Service believed enter the wilderness by watercraft (Table

1).

Management was concerned with the perceived continued illegal use of

motorized

vehicles such as watercraft, and especially, snowmobiles. There

was

also a concern about indiscreet nude sunbathers and nude windsurfers

who

were thought to create discomfort for others, especially families with

children. Encounters among trail hikers and campers were

estimated

by managers to be “high”. Managers described a wide variety of

user

types including day users, boaters of all types, nude sunbathers, horse

riders, motorized vehicle users, large groups, and others whose

presence

and/or activity might conflict with other users. To managers,

ecological

and scientific values were the primary characteristics of wilderness

that

needed to be protected (Gobster, 1993; U.S. Forest Service, n.d.).

Managers

suggested, based on their use estimates, that "there could be a new

class

called 'Urban' Wilderness for the Nordhouse Dunes from mid-June through

Labor Day" (Ingells, 1991).

Table 1 - Comparison of manager versus user views

of

Nordhouse Dunes Wilderness, Michigan (1995)

|

Category

|

Managers' Viewsa

|

Visitors' Views

|

| Recreational Use |

Overused and overcrowded |

Not overcrowded (83%)b |

|

Visitors do not find solitude |

Place to be alone (87%)b |

|

15-20,000visitors/year |

7-10,000 visitors/year |

|

Many conflicts |

Conflicts minimal |

|

Nudism a serious problem |

Nudism not a problem

Minor activity (13%)c

Major activity (6%)d

Expectations nonexistent or not exceeded |

|

Significant problems with watercraft |

Watercraft on beach not a problem |

|

|

Few watercraft users (20%)b |

|

|

No watercraft observed by interviewers |

| Management controls |

Need more controls on horses, nudism |

Current controls adequate |

|

|

Reduce control (10%)b |

|

|

Increase controls IF overuse occurs (40%)b |

|

|

Experience good (95%)b |

|

|

Wilderness quality staying the same or improving (89%)b |

| Meanings |

Reclassify as “urban wilderness” |

Definitions of wilderness consistent with Wilderness Act of

1964 (83%):e

• Forces of nature predominate

• Minimal human influence |

|

|

Meanings outside of Wilderness Act (17%):e

• Spiritual/tranquility

• Sense of being away |

|

|

Overall, Nordhouse meets my personal definition of wilderness

(86%)b |

|

|

|

a Manager's views were not based on a random sample of

managers

but upon qualitative data from personal communications, transcribed

meeting

minutes (Gobster 1993), Nordhouse Dunes published literature (US Forest

Service, n.d.) and newspaper articles (e.g., Ingells, 1991)

b ( ) = percentage of visitors agreeing with the statement

c 19% participated in nude sunbathing;13% listed it as a

secondary (“minor”) activity

d 6% participating in nude sunbathing as the primary

(“major”)

reason for visiting the area

e 83% of visitor definitions matched Wilderness Act legal

definitions closely; 17% were personal definitions not specifically

stated

in the Wilderness Act

User Perceptions Of Nordhouse Dunes

In contrast to manager perceptions, 83% of the visitors

to Nordhouse Dunes said that the area was not overcrowded and 87% felt

Nordhouse was a place to be alone (Table 1). Actual use was

estimated

to be 7-10,000 visitors annually or approximately half of manager

estimates

(McDonough et.al., 1995). Visitors felt that with the exception

of

hunting, visitor conflicts were minimal. Visitors did not consider

nudism--seen

by the managers as a serious problem for other visitors--to be a

problem

at all. Nineteen percent (19%) of visitors said they participated

in nude sunbathing at Nordhouse Dunes. Thirteen percent (13%) listed

nude

sunbathing as a minor activity, while 6% listed it as a major

activity.

In response to the question, “how did the number of nude sunbathers you

saw compare to the number you expected to see”, 1% said they saw more

nude

sunbathers than expected, 17% said they saw what they expected, a third

said they saw fewer than expected, and half had no expectation

regarding

nude sunbathing. Furthermore, visitors did not note problems with

watercraft on the beach. Less than 20% reported using a boat of

any

kind adjacent to the wilderness and none were observed by interviewers.

With respect to management controls, most visitors

felt management controls were adequate. In fact, 10% wanted management

controls reduced. Only 6% of visitors wanted management to reduce

visitation. However, 40% wanted more management controls if

overuse

began to occur. Ninety five percent (95%) of visitors rated their

experience

at Nordhouse Dunes as very good or good and 89% of repeat visitors said

wilderness quality was either stable or improving.

In an open-ended question, respondents were asked

to describe what wilderness meant to them. Of the responses, 83% were

well

within the bounds of the Wilderness Act of 1964 (McDonough et al.,

1995).

Many of their definitions were consistent with those of managers,

particularly

with regards to wilderness as a place where the forces of nature

predominate

and where the influence of humans was minimal. Visitors also

mentioned

spiritual values and a sense of being away. Unlike managers,

visitors

infrequently stated ecological and scientific values as part of their

definitions.

Another discrepancy was that minimal human influence had a broader

meaning

for visitors ranging from completely untouched by humans to rustic

accommodations.

Overall, 86% of the visitors agreed that Nordhouse Dunes met their

personal

definition of a wilderness. The visitor data did not support

management’s

contention that Nordhouse should be reclassified as an “urban

wilderness”.

Applying the Mutual Self-interest Framework

Managers see Nordhouse through the screen of their

training and experience and so interpret what they see as overcrowded

and

problematic. They then tend to assume that visitors feel

the

same way. Visitors share with managers some of the same meanings

of wilderness but did not interpret the current conditions as reasons

for

alarm. These differences in interpretation of current conditions

pose critical questions relative to the LAC process as well as other

modes

of public input. How can managers understand the causes of the

discrepancy

between their perspective and that of the visitors? For example,

which of their proposals are a reflection of their technical expertise

and which are a reflection of their personal values? How can

managers

recognize the mutual self-interest they have with visitors who share

wilderness

definitions with them, think Nordhouse meets these definitions and want

to see it remain in its current condition? What are the

appropriate

management responses once awareness of these differences and

similarities

occurs?

One way to answer these questions is to reassess

management issues at Nordhouse Dunes in a mutual self-interest

framework.

As described earlier, the proposed framework builds upon the work of

Perloff

(1987) and Heifitz and Sinder (1988). The mutual self-interest

framework

has five parts (Figure 1). Part A is visitor self-interest, B is

manager

self-interest based on technical expertise, C is manager self-interest

based on personal values and D is mutual self-interest. As

defined

by Perloff (1987), manager self-interest manifests itself as “social

support”

provided by the state. Following Perloff’s reasoning, when social

support becomes excessive or inappropriate, dependencies develop and

visitors

no longer feel personal responsibility for resource

management.

Visitor self-interest may manifest itself as complaints to agency

officials

and legislators, rule-breaking, resource damage and, in the extreme,

lawsuits

which temporarily or permanently restrain management activity.

Mutual

self-interest is analogous to Hardin’s (1968) “mutual coercion” in the

sense that “democracy is governed by restrictive laws that can be

legitimately described as exerting mutual coercion, mutually agreed

upon”

(Hardin, 1993: 297). The authors’ conceptualization of mutual

self-interest

differs from Hardin in that rules and regulations may be developed

jointly

by manager and visitor dialogue rather than by laws and

litigation.

One example is visitor/manager agreement on rules and restrictions

pertaining

to recreational activities at Cape Cod National Seashore (Canzanelli

&

Reynolds, 1996). In the case of Cape Cod, visitors

promulgated

rules that were more restrictive than those that the managers were

considering.

A similar event—user groups agreeing upon more restrictive regulations

than those initially offered by managers--occurred at the Charles C.

Deam

Wilderness on the Hoosier (Indiana) National Forest (Slover, 1996).

In the following discussion, we demonstrate how the

mutual self-interest framework works by applying it to four potential

conflicts

at from Nordhouse Dunes. Three (crowding, horses, and nude

sunbathing)

were identified by managers as significant and the fourth, hunting, was

identified by visitors.

Crowding. The issue of crowding has two components:

biophysical

(e.g., potential ecological damage to the wilderness from overuse) and

social (e.g., the feeling of being crowded). Managers believe

that

Nordhouse Dunes is crowded and that crowding is affecting the quality

of

visitor experiences. These perceptions are based partially on

inaccurate

estimates of actual use (B in Fig. 1) and partially on manager’s own

definitions

of crowding (C in Fig. 1). Visitors do not think Nordhouse Dunes

is crowded and they rate their experiences very highly (A in Fig.

1).

However, they do not want to see use increase. Mutual

self-interest

lies not in controlling the current “crowding” which visitors do not

perceive

but rather in addressing two questions. First, can use levels be

kept at their current level? Second, what should be done in the

future

if use levels do rise? To hold future use to current levels,

managers

must first apply their technical expertise to monitor use closely and

carefully

(B in Fig. 1). If use rises beyond current levels, managers and

visitors

will need to develop mutual use restriction strategies (D in Fig. 1).

In

addition, managers and visitors agree that some heavily used areas need

to be managed (lower use, rehabilitate). Due to their technical

expertise

(B in Fig. 1), managers are best at identifying ecological damage along

trails and in campsites. If ecological damage is identified by

managers

and exceeds certain standards, a mutual self-interest approach would

suggest

that managers and users develop cooperative regulations.

Horses. At the time of this study, managers were

proposing

regulations because they projected horse use as a future problem (B and

C in Fig. 1). Visitors did not see this as a problem yet and, in

fact, little horse use occurs in the wilderness area (A in Fig.

1).

Manager training is in identifying ecological damage (B in Fi.g. 1).

Visitor

self-interest is in maintaining the current condition as it meets their

needs and their definition of wilderness. As with crowding,

mutual

self-interest would be realized in two steps: (1) ecological damage

begins

to occur and is identified and documented by managers (B in Fig. 1),

and

(2) visitors and managers participate in cooperative development of

regulations

(D in Fig. 1).

Nude sunbathing. Managers define this as a problem for

visitors. The data as well as comments written on the survey

indicate

nude sunbathing is not a concern of visitors. The definition of a

“problem” is likely a reflection of manager values (C in Fig. 1) rather

than technical expertise (B in Fig. 1) as nude sunbathing causes little

damage to the resource and in this case, to visitor experiences.

Increasing regulation by managers would have a negative effect on

visitor

self-interest, as visitors do not want more regulation (A in Fig.

1).

Mutual self-interest in regulating nude sunbathing (D in Fig. 1) might

exist if visitor protection or safety issues existed but they do

not.

There appears to be little mutual self-interest. Thus, no

regulation

is necessary, as the problem does not appear to exist for visitors.

Hunting. In this case, there are three sets of

self-interest

instead of two as visitor self-interest is divided. While only

19%

of the visitors to Nordhouse Dunes are hunters, the highest

concentrations

of visitors occur during firearm deer season (McDonough et al.,

1995).

The views of hunters and nonhunters diverge substantially. For

example,

54% of nonhunting visitors agreed that there were too many hunters and

that hunting should be banned. On the other hand, only 15% of

hunters

agreed that there should be fewer hunters and 7% felt that hunting

should

be banned. Legally, hunting is allowed and so managers must

provide

for this opportunity (B in Fig. 1) regardless of personal self-interest

(C in Fig. 1). Most hunters are present only during firearm deer

season so there is no face-to-face conflict as user groups who object

are

separated in time. In fact, most of the people who objected to

hunting

in the wilderness area were visiting in the summer months while firearm

deer season is in November. It appears that both sets of visitor

self-interest

(A in Fig. 1) are being met through the separation in time. If

nonhunting

use pressure increases in the fall, mutual self-interest might be

achieved

by having all three groups decide how to reduce conflict (D in Fig.

1).

That is, the principle of mutual coercion would suggest that all

parties

participate in cooperative development of further hunting regulations.

Conclusions

The purpose of this paper was to propose and test

a model for improving conflict resolution in wilderness

management.

The model integrates the powerful motivator, self-interest, into the

Limits

of Acceptable Change planning process and calls upon managers to

facilitate

public discourse with the goal of finding areas of mutual self-interest

when determining appropriate management strategies. As recommended by

the

literature on participatory democracy, such a model asks public

managers

to manage citizen participation as actively and purposefully as they

manage

natural resources. To the extent that this framework is

implemented,

resource managers follow another recommendation of the literature,

which

is the evolution from autocrats to facilitators of public

responsibility

in resource management. The upshot pertains to a third

recommendation

of the literature, experimentation with collaborative management.

Collaboration is not a panacea for solving messy

resource management issues, and it is not a way of relieving public

managers

of their obligations to make difficult decisions. Nonetheless,

collaborative

efforts can at least solve some of the problems, avoid some of the

costs

(social as well as financial) of litigation, propose innovations in

public

land management, and contribute to direct democracy (Brick et al.,

2001).

Collaboration is increasing becoming functionally integrated into the

natural

resource policy making process in the U.S. (Wellman and Propst, in

press).

Collaboration is fundamentally different from traditional

public involvement processes in which the flow of information is

usually

one-way, most often in the form of public hearings or requests for

written

comments on draft plans. The basis of the mutual self-interest model is

two-way communications. As with other collaborative processes,

there

is no guarantee of a short or predictable outcome. We recommend that

resource

managers implement and fulfill the challenges of the new role implied

by

this and other participatory democracy models by conducting small

experiments

in expanding public discourse and developing processes with which they

are most comfortable. The Nordhouse Dunes case exemplifies one

way

in which managers are realizing their new role.

At Nordhouse Dunes, the process toward identifying

and implementing points of mutual self-interest has been ongoing since

the researchers presented the results of this study.

Because

of the LAC study, managers obtained a great deal of empirical data

about

the values, interests, expectations and characteristics of Nordhouse

visitors.

Having been exposed to these data, managers identified their own

self-interest

by engaging researchers in a dialogue, which attempted to clarify the

distinction

between personal values and technical expertise2.

This dialogue resulted in a formal presentation at a national

conference

during which time both researchers and managers demonstrated how the

social

science data from the LAC study had affected management decisions by

refocusing

resources on areas of mutual interest (Propst, 1998). In

addition,

managers have engaged visitors in a dialogue about the results of the

study

and the need for use restrictions pertaining to specific behaviors in

specific

areas of the wilderness (John Hojonowski, personal communication,

February

19, 2002).

Examining 22 years worth of evidence pertaining to

common property resource management, Feeny et al. (1990) conclude that

Hardin’s insights were critical but insufficient. According to

the

authors, Hardin’s model overlooks the enormous role of nongovernmental

institutional restrictions and cultural influences on behavior.

For

example, shared governance or state regulation--jointly with user

self-management--are

viable options (Feeny et al. 1990).

The latter option, state regulation jointly with

user self-management, can be implemented by taking advantage of a

common

human trait: self-interest. The self-interest framework posits

that

mutual self-interest, the agreement zone in Figure 1, is achieved when

managers and visitors mutually agree upon the actions necessary to

achieve

certain visitor experiences or restrict certain visitor

behaviors.

This approach calls for managers to examine their own values and when

they

conflict with user values, seek a civic conversation that leads to

agreement

about appropriate strategies. Management’s role is then to apply

its strength--technical expertise--to the implementation of those

strategies.

Reinforcing visitor self-interest through collaborative decisionmaking

will transfer more personal responsibility to the users and diminish

the

view of wilderness as a “commons” than must be protected from humans

who

use it3. Public participation

will

be ineffective unless all three types of self-interest are given

balanced

attention and institutionalized into the policies, educational programs

and actions that affect natural resource decisionmaking. The mutual

self-interest

model holds much promise for conflict resolution—before the conflicts

begin.

Literature Cited

Behn, R. (1988). Management by groping along. Journal of Policy

Analysis and Management, 7(4), 643-663.

Brick, P., Snow, D., & Van De Wetering, S. (Eds.). (2001). Across

the Great Divide: Explorations in collaborative conservation and the

American

West.

Washington, DC: Island Press.

Bullis, C.A. & Tompkins, P.K. (1989). The forest ranger

revisited:

A study of control practices and identification. Communication Monographs,

56, 287-306.

<>Bultena, G.L. (1974). Self-interest groups and human emotion as

adaptive

mechanisms. In D. R. Field, J.C. Barron & B.F. Long (Eds.), Water

and community

development: Social and economic perspectives.

(pp. 151-169). Ann Arbor, MI: Ann Arbor Science.

Canzanelli, L. & Reynolds, M. (1996). Negotiated rule making as

a resource and visitor management tool. Park Science, 16(2), 1-3.

Clare Cooper Marcus, C. A. F. (1990). People places: design guidelines

for urban open space. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Clark, T.W., Willard, A.R., & Cromley, C.M. (Eds.). (2000). Foundations

of natural resources policy and management. New Haven: Yale

University

Press.

Cronon, W. (1995). The trouble with wilderness. The New York Times

Magazine, Aug. 16, 1995, section 6.

De Young, R. & Kaplan, S. (1988). On averting the tragedy of the

commons. Environmental Management, 12(3),

273-283.

Downs, R.M. & Stea, D. (Eds). (1973). Image and environment:

Cognitive mapping and spatial behavior. Chicago: Aldine.

Feeny, D., Berkes, F., McCay, B. J., & Acheson, J. M. (1990).

The

tragedy of the commons: Twenty-two years later. Human Ecology,

18(1), 1-19.

Gilovich, T. (1991). How we

know what isn’t so: The fallibility

of human reason in everyday life. New York: The Free

Press.

Gobster, P. (1993). Notes on January 27 meeting for proposed

Nordhouse

Dunes study. Unpublished meeting minutes. Chicago, IL: USDA Forest

Service,

North

Central

Forest Experiment Station.

Halprin, L. & Burns, J. (1974). Taking part: a workshop approach

to collective creativity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. Science,

162, 1243-1248.

Hardin, G. & Baden, J. (Eds.). (1977). Managing the commons.

San Francisco: Freemen.

Hardin, G. (1993). Living within

limits: Ecology, economic and population

taboos. Oxford University Press, New York.

Heifitz, R.A. & Sinder, R. M. (1988). Political leadership:

Managing

the public’s problem solving. In Reich, R.B. (Ed.), The power

of public ideas (pp. 179-205).

Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press.

Henderson, K. A. (1991).

Dimensions of choice: A qualitative approach

to recreation, parks, and leisure research. State College, PA:

Venture.

Hester, R. T. (1984). Planning

neighborhood space with people.

New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Hultsman, J., Cottrell, R.L., & Zales-Hultsman, W. (1987). Planning

parks for people. State College, PA: Venture.

Ingells, N. (1991). Parks in peril. Lansing State Journal, July

7, 1D, 5D.

Kaplan, S. & Kaplan, R. (1983). Cognition and Environment: Functioning

in an Uncertain World. Ann Arbor, MI: Ulrich’s.

Kaplan, S. & Peterson, C. (1993). Health and environment: A

psychological

analysis. Landscape and Urban Planning,

26, 17-23.

Kaplan, R., Kaplan, S., & Ryan, R.L. (1998). With people in mind:

Design and management of everyday nature. Washington, DC: Island

Press.

Knight, R.L. & Landres, P.B. (Eds.). (1998). Stewardship across

boundaries. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Kotulak, R. (1996). Inside the

brain: Revolutionary discoveries of

how the mind works. Kansas City: Andrews and McNeel.

Leopold, A. (1966). Sand

County almanac. New York: Ballantine.

Lindblom, C.E. (1979). Still muddling, not yet through. Public Administration

Review, 39, 517-526.

Lynch, K. (1960). The image of

the city. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Magill, A.W. (1988). Natural resource professionals: The reluctant

public

servants. The Environmental

Professional, 10, 295-303.

McDonough, M.H., Propst, D.B. & Wiita, A.L. (1995). Nordhouse

Dunes Wilderness user study. Final Report. Chicago, IL:

U.S.D.A.

Forest Service, North

Central

Experiment Station and East Lansing, MI:

Michigan State University, Department of Forestry.

Orren, G.R. (1988). Beyond self-interest. In Reich, R.B. (Ed.), The

power of public ideas (pp.13-30). Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University

Press.

Perloff, R. (1987). Self-interest and personal responsibility redux.

American

Psychologist, 42(1),

3-11.

Peters, T.J. & Waterman, R.H. (1982). In search of excellence:

Lessons from America’s best-run companies. New York:

Harper and

Row.

Propst, D.B. (1998). “Nordhouse

Dunes Wilderness user study: Management

and LAC implications.” Society of American Foresters National

Convention,

Sept.

19-23,

Traverse City, MI.

Propst, D.B., Wellman, J.D., Campa, H.R. III, & McDonough, M.H.

(2000). Citizen participation trends and their educational implications

for natural resource

professionals. In D.W. Lime, W.C. Gartner, &

J. Thompson (Eds.), Trends in

outdoor recreation and tourism (pp.

383-393). Wallingford, Oxon, UK: CAB

International.

Propst, D.B. & Bentley, S.C. (2000). Trends in citizen

participation

in outdoor recreation and resource management: Manager vs. citizen

perspectives.

In

Proceedings of the Fifth Outdoor

Recreation and

Tourism Trends Symposium (pp. 202-212). East Lansing, MI:

Michigan

State University, Department of Park,

Recreation

and Tourism Resources and Michigan Agricultural

Experiment Station.

Reich, R. B. (Ed.). (1988). The

power of public ideas. Cambridge,

MA:Harvard University Press.

Shannon, M.A. (1991). Resource managers as policy entrerpreneurs:

Governance

challenges of the urban-forest interface. Journal of Forestry, 89(6),

27-30.

Shepherd, G. (1988). The reality

of the commons: Answering Hardin

from Somalia. Network Paper 6d. London: Overseas

Development

Institute.

Sirmon, J.M. (1993). National leadership. In J.K. Berry & J.C.

Gordon

(Eds.), Environmental leadership:

Developing effective skills and styles

(pp. 165-185).

Washington, DC: Island Press.

Sirmon, J. M., Shands, W.E., & Liggitt, C. (1993). Communities

of

interest and open decision-making. Journal of Forestry, (91)7, 17-21.

Stankey, G.H., Cole, D.N., Lucas, R.C., Petersen, M.E., &

Frissell,

S.S. (1985). The limits of acceptable change (LAC) system for

wilderness

planning. General

Technical Report INT-176. Ogden, UT: USDA

Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station.

Slover, B. L. (1996). A music of opinions: Collaborative planning

for

the Charles C. Deam Wilderness. Journal

of Forestry, 94(3), 18-23

Tipple, T.J. & Wellman, J.D. (1989). Life in the fishbowl:

Public

participation rewrites public foresters’ job descriptions. Journal of

Forestry, 87(3), 24-30.

Wamsley, G.L. (1990). Refounding

Public Administration. Sage,

Newbury Park, CA.

Weiner, J. (1995). Common property resource management and northern

protected areas. In D.L. Peterson & D.R. Johnson (Eds.), Human

ecology and climate

change: People and resources

in the Far North

(pp. 207-217). New York: Taylor & Francis.

Wellman, J.D. & Tipple, T.J. (1990). Public forestry and direct

democracy. The Environmental

Professional, 12, 77-86.

Wellman, J.D. & Tipple, T.J. (1992). Working with the

community:

A conceptual framework for urban forest managers. Forest Policy

Center Report 92-3.

Washington, DC: American Forests.

Wellman, J.D. & Tipple, T.J. (1993). Governance in the

wildland-urban

interface: A normative guide for natural resource managers. In

A.W.

Ewert, D.J. Chavez,

& A.W.

Magill (Eds.), Culture, Conflict and

Communication in the Wildland-Urban Interface (pp.

337-347).

Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Wellman, J. D. and Propst, D.B. (in press). Wildland recreation policy,

2nd Edition. Malabar, FL: Krieger.

Wiita, A. L. (1998). Evaluation

of managers’ and visitors’ perceptions

of wilderness conditions at the Nordhouse Dunes Wilderness Area.

Unpublished

MS Thesis.

East

Lansing, MI: Michigan State University, Department

of Forestry.

Wondolleck, J. M. (1988). Public

lands conflict and resolution: Managing

national forest disputes. Plenum, New York.

U.S. Forest Service. (no date). Welcome

to Nordhouse Dunes Wilderness.

Unpublished transcript of slide presentation. Manistee, MI: USDA Forest

Service,

Manistee

Ranger District.

1 Heifitz and Sinder’s “communities of

interest”

model has been applied to natural resource planning in a preliminary

manner

with mixed results (Sirmon, 1993; Sirmon et al., 1993; Brick et al.,

2001).

2 After managers had time to digest the

data

upon which this study is based, they participated in an interactive

session

with the principal investigators. During this session, managers

worked

in small groups to develop management implications based on the new

data.

Each group then presented its implications to the entire group for

further

discussion and a revised list of implications for crowding, horse use,

nude sunbathing, and hunting were developed (McDonough, Propst, &

Wiita,

1995).

3 Feeny et al. (1990) emphasize the

importance

of clearly distinguishing between the type of common property

resources--open

access, common property, private property, state property--when

evaluating

Hardin. Feeny et. al and others (e.g., Weiner, 1995) make

the

case that Hardin’s original chastisement of human inability to manage

the

commons referred primarily to open access resources (e.g., the Internet

or fisheries where it is almost impossible to control access).

The

Nordhouse Dunes Wilderness would fall under the category of “state

property”.

We are aware of the differences among types of common property

resources,

but argue that many in the natural resource management profession feel

that humans are incapable of adequately managing state as well as open

access property.