Contact information:

Benoni Amsden

Department of Rural Sociology

111 Armsby Building

Penn State University

University Park, PA 16802

bla144@psu.edu

Abstract

Long distance hiking trails are subject to the pressures of both human

visitors and management conflicts. Resource conservation, volunteer

management,

and ecological concerns are only a few of the topics occupying the

organizations

that manage these trails. With a work force made up mainly of

volunteers,

these groups adopt as their mission both the maintenance of many miles

of trail, and the protection of the recreation opportunities those

trails

provide. Our qualitative, case study approach examined one of these

trail

management organizations, assessing the extent to which it has adopted

and implemented best practices for managing its volunteer workforce.

Using

this organization as a template, we also explored if and how best

practices

can be used to measure the effectiveness of the volunteer programs on

which

these types of organizations so heavily rely. Our findings revealed

that

best practices, when implemented, 1) result in a stronger volunteer

workforce,

and 2) are important ingredients in an effectiveness model designed

specifically

for trail management organizations. Understanding and implementing best

practices for volunteer management is of growing importance in an era

of

shrinking budgets and heightened accountability.

Introduction

Throughout the United States, long

distance

hiking trails are subject to the pressures of both human visitors and

management

conflicts (Appalachian Mountain Club, 2003). Each year, nearly four

million

individuals hike some portion of the 2,160 mile Appalachian Trail,

while

almost 2,300 hikers have tramped the entire length of Vermont’s

270-mile

Long Trail (Appalachian Trail Club, 2005; Green Mountain Club, 2005).

As

a result, the oversight and maintenance of these trails has become an

example

of a resource issue affecting a broad range of interests. Landscape

conservation,

volunteer management, and ecological concerns are only a few of the

topics

that occupy organizations such as the North Country Trail Association,

the Green Mountain Club, and the Appalachian Trail Conference. Often

working

in tandem with federal agencies such as the National Park Service or

the

U.S. Forest Service, these non-profit groups adopt as their mission

both

the maintenance of many miles of trail, and the protection of the

recreation

opportunities those trails provide.

One cornerstone of successful non-profit trail groups is a strong

and loyal volunteer workforce. Research in contexts outside of outdoor

recreation management has shown that successful volunteer programs

operate

around a carefully planned and implemented set of best practices

(Brudney,

1999). What is needed, however, is a greater understanding of how

non-profit

trail groups manage their essential core of volunteers.

The study reported herein has two purposes. The first purpose is to

examine the extent to which a large, recreational trail management

organization

is adopting and implementing established best practices for managing

its

volunteer workforce. The second is to reveal if and how these best

practices

can be used to help such an organization measure the effectiveness of

its

volunteer program.

Volunteers and their management

In 2004, nearly 65 million American

adults

participated in some form of volunteering (U.S. Department of Labor

Statistics,

2005). During the course of the year, these volunteers performed an

average

of slightly more that 52 hours of service, with a total estimated value

of $239 billion ( Independent Sector, 2005; U.S. Department of Labor

Statistics,

2005). As budgets shrink and services decline, this valuable work is of

increasing importance to those who manage recreation resources.

For example, the organizations that oversee recreational hiking

trails

rely heavily on their volunteer workforce (Hardy, Larose, & Rose,

2003).

In 2001, the 31 groups which work together to maintain the Appalachian

Trail under the oversight of the Appalachian Trail Conference enjoyed

the

services of over 5,000 volunteers, who contributed almost 187,000 hours

(Appalachian Trail Conference, 2005). These volunteers participated in

important activities such as trail oversight and maintenance, shelter

adoption,

boundary monitoring, and even performed office-based administrative

work

(Hardy et al., 2003).

The literature surrounding volunteering and public participation has

provided a multitude of definitions. Propst, Jackson, and McDonough

(2004)

suggest that researchers tend to focus on certain definitions based on

their disciplinary training. For example, researchers who focus on

public

participation are grounded in “participatory democracy, civic

engagement,

social capital, international development and other theoretical

frameworks

common in political science and sociology”, while those who study

volunteering

“rely on theories from psychology” (Propst et al., 2004, p.405).

Definitions of volunteering and public participation vary in terms

of

the extent to which citizens actually seek out opportunities to donate

their time and energy. While volunteering typically provides services

that

are “professionally initiated and defined”, citizen participation tends

to be more of a “voluntary activity that is individually initiated and

defined” (Propst et al., 2004, p.405).

Because their work is so important, volunteers are being delegated a

wide range of responsibilities(Cuskelly, Hoye, & Auld, 2006;

Grossman

& Furano, 1999; Stebbins & Graham, 2004). These

responsibilities

can be arrayed along a spectrum to reflect the degree of volunteer

power

over decision-making (Propst et al., 2005). The low-power end of the

spectrum

includes passive volunteer behaviors often directed by others

(McDonough

& Wheeler, 1998; Propst et al., 2004). The high-power end of the

spectrum,

on the other hand, involves some level of shared authority in policy

making,

planning or management, where a volunteer assumes some influence over

organizational

objectives and outcomes (McDonough & Wheeler, 1998; Propst et al.,

2004).

Best practices

The rise in volunteerism has shepherded research activity in such

realms

as perceptions of fairness (Smith & McDonough, 2001), volunteering

as serious leisure (Arai & Pedlar, 1997; Stebbins, 1992),

volunteering

as a function of place attachment (Payton, Fulton, & Anderson,

2005)

and volunteer motivations, expectations, and psychological benefits

(Farmer

& Fedor, 1999; Grese, Kaplan, Ryan, & Buxton, 2000; Jackson,

2003;

Liao-Troth, 2001; Propst et al., 2004; Schroeder, 2000). As one result,

the values, experiences, and expectations of volunteers are beginning

to

be incorporated into the management strategies of recreation

organizations

(Schroeder, 2000).

For instance, academic research and practitioner literature

addressing

volunteer management (Barnett, 2002; Bradner, 1993; Campion Devney,

1992;

Clarke & McCool, 1996; Forsyth, 1999; Govekar & Govekar, 2002;

Gratton & Ghoshal, 2003; Lee & Catagnus, 1999; Pharoah, 1997;

Silverberg,

2004) conclude that the most successful volunteer programs operate

around

a planned, established set of best practices (Brudney, 1999; Ellis,

1996;

McCurley & Lynch, 1996; Wilson, 1978). Receiving consistent support

throughout the literature on successful volunteer management are best

practices

that:

1) Commit

to a volunteer program: It is important for organizations to have

in

place a structure that supports the oversight of the volunteer

workforce

(Ellis, 1996).

2) Provide

written policies to govern the program: “The[se] policies will

allow

the manager of volunteers to develop a consistent pattern of volunteer

involvement, and will provide assistance in dealing with problem

situations”

(McCurley & Lynch, 1996, p.104).

3) Create

job descriptions: “The job description defines the role,

relationships,

responsibilities, obligations, content, power, and privileges of a

volunteer

position”

(Heidrich, 1990, p.73).

Job descriptions can also be used for recruiting purposes

(Brudney, 1999).

4) Provide

support activities for volunteers: These activities should consist

not only of orienting the volunteer to the organization’s methods and

structures,

but should demonstrate the willingness on the part of the manager to

provide

logistical support to volunteers

(Brudney, 1999; Ellis, 1996; McCurley & Lynch, 1996).

5) Empower

volunteers: Empowerment is the process of invigorating volunteers

by

empowering them through teaching, training, and experience so that they

can work independently, manage other volunteers, or engage in decision

making

(Brudney, 1999; Ellis, 1996).

6)

Evaluate

work performed:

Evaluating volunteers consists of keeping records of the type and

amount

of work performed, observing whether or not work performance is in line

with stated goals, providing praise for a job well done or remediation

of a poor job (Brudney, 1999).

Applications of volunteer research

Volunteer management has been previously researched in many

different

contexts. For example, Wilson and Pimm (1996) studied personnel

management

in both the corporate and non-profit sectors, focusing specifically on

volunteer motivation, benefits, and management strategies. Their

research

found that the majority of volunteer workforces are poorly managed due

to the lack of organizational adherence to conventional business

management

methods (Wilson and Pimm, 1996).

Other

research has evaluated effective volunteer practices within broader

contexts

such as education, finding that while volunteers may be given greater

responsibility,

their effectiveness depends on an infrastructure built around

selection,

training, communication and support (Grossman

& Furano, 1999).

One outcome of these research findings has been the

development of professional management tools such as the Volunteer

Functions

Inventory. The VFI is designed to measure volunteer motivations in six

distinct psychological areas:values,

understanding,

career, social, esteem, and protective (Clary,

Snyder, & Ridge, 1992).

Each area is assigned a score based upon the volunteer’s responses to a

survey. Assessment of these scores helps volunteer managers optimize

three

areas of volunteer management: recruitment, placement, and

retention (Clary

et al., 1992, p.23).

In summary, research surrounding volunteers and their

management has shown that strategic volunteer management results in

beneficial

outcomes, which, in turn, serve as indicators of organizational

effectiveness

in managing volunteers. Tools such as best practices or the VFI are all

situation-specific and address the volunteer experience in a piecemeal

fashion. Lacking is a more systematic and holistic approach to

measuring

effectiveness that can be applied to a variety of volunteer management

situations and organizations.

Conceptual Framework

Any implementation of volunteer management

strategies

requires both a determination of how well the volunteer program will

work,

and the impact of management changes on overall effectiveness. Could a

model correlating employee management and organizational performance in

a business environment be useful and appropriate for measuring

volunteer

management in a non-profit, natural-resource based recreation

environment?

We propose a holistic measurement of effectiveness by adapting an

existing

evaluation framework (Ramlall 2003) that has been designed to assess

the

effectiveness of human resource management strategies. Specifically,

Ramlall

(2003) notes a strong correlation between management of paid employees

and the overall performance of the organization. It seems logical,

then,

to assume that this correlation will also apply to the management of

volunteers

and the performance of the non-profit organization.

Ramlall’s

(2003) framework is organized into human resource activities (HR

management

clusters) and their associated outcomes. This framework can be applied

to the management of volunteers by assigning each of the six volunteer

management best practices from the literature - described above - to a

relevant Human Resource (HR) management cluster in Table 1, and

assessing

the associated outcomes. For example, the best practice involving the

creation

of job descriptions can most appropriately be linked to the management

cluster “acquisition of employees”, because the outcomes are relevant

to

both volunteer and employee management. Furthermore, the outcomes

associated

with successful acquisition of employees – short period of time to

hire,

effective contribution of new hires, adequate number of qualified

applicants

– are appropriate when applied to the recruitment of volunteers. Hence,

adequate volunteer job descriptions can result in the successful

acquisition

of an effective volunteer workforce.

To craft an even better fit, however, between Ramlall’s model and

the

other best practices, some modifications to his framework are

necessary.

Each of the seven management clusters and their associated outcomes

must

be modified to transition the model from a corporate, business

standpoint

to a non-profit, volunteer, trail management perspective. This

transition

can be accomplished by removing outcomes that do not apply to

volunteers,

such as those associated with hiring, customer service, and financial

remuneration.

Consistent with the volunteer literature (Brudney, 1999; Ellis, 1996;

McCurley

& Lynch, 1996) , terminology was chosen to better reflect the

volunteer

context that we are trying to assess. The resulting modifications of

Ramlall’s

framework are displayed in Table 1:

Table

1: Modification of Ramlall’s Effectiveness Model with Modified Outcomes

Based on the Volunteer Management Literature

|

Management

Cluster

|

Original

Human

Resource Outcome

|

Modified

Volunteer

Outcome

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.

Strategic Planning

|

a)

Analysis, decisions,

and actions needed to create and sustain competitive advantage

|

a)

Analysis, decisions,

and actions needed to create and sustain a functional volunteer program

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.

Acquisition of

Employees

|

a)

Effective contribution

of new employees to business strategy implementation, b) Planning

process,

advertising, and recruitment sources support business strategy, c)

Interviews

effective in selecting right candidates

|

a)

“Effective contribution”

of new volunteers, b) “planning process, advertising, and recruitment

sources”

should fit the organization’s management strategy

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. Training

&

Development

|

a) Positive

change

in attitude of participants, b) Increased expertise in areas applicable

to job, c) Opportunities to practice newly acquired skills on the job,

d) Support from peers, supervisors, and others in using knowledge

gained

|

a)

Increased expertise

in areas applicable to job, b) opportunities to practice newly acquired

skills on the job, c) support from peers, supervisors, and others in

using

knowledge gained

|

|

|

|

|

|

4.

Organizational

Change & Development

|

a) Higher

levels

of productivity, quality of products and services, b) Positive change

in

responsiveness in meeting customer needs, c) Culture reflects

organization

and supports business strategy, d) Fluid organization structures

|

a) Higher

levels

of productivity, b) quality of work performed, c) fluid organizational

structures

|

|

|

|

|

|

5.

Performance Management

|

a)

Each position and task supports strategic business objectives, b)

Effective

process for maximizing performance

|

a) Each

volunteer

“position and task supports strategic objectives, b) effective process

for maximizing performance

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. Reward

System

|

a) Reward

system

motivates increased performance, b) Incentives provided to achieve

individual

and organizational behaviors aligned with business strategies and

investments

|

a) reward

system

motivates increased performance

|

|

|

|

|

|

7.

Organization Behavior

& Theory

|

a) Employee

behaviors

reflect desired organizational culture and alignment with business

strategy

|

a)

Behaviors reflect

desired organizational culture and alignment with organizational

strategy

|

Research

questions

It has been suggested that non-profit, trail

management organizations rely heavily on their volunteer workforce

(Hardy, Larose, & Rose, 2003).

Furthermore, formal implementation of theoretical best practices for

volunteer

management has yet to be considered in the context of these non-profit

trail organizations. The modified Ramlall framework (Table 1) could

fill

this gap by creating a model designed to measure the effectiveness of

volunteer

programs using best practices as a resource for trail managers.

Therefore,

this research attempts to answer the following questions:

1) What is the extent to which a

non-profit

trail management organization has adopted and implemented best

practices

for managing volunteers?

2) Is the

suggested modification to Ramlall’s model relevant to this trail

organization

in terms of its ability to assess the effectiveness of its volunteer

program?

Although trail organizations such as the one in this study typically

rely more heavily upon volunteers than their federal counterparts such

as the National Park Service or U.S. Forest Service, the lessons

learned

will be of use to managers and coordinators of volunteers throughout

the

public and private sectors, in addition to profit and non-profit

organizations.

Procedures

Since the extent to which the best practices outlined in the research

literature may be interpreted differently by different individuals, a

traditional

quantitative methodology consisting of a survey, for example, may

overlook

important categorical distinctions (Henderson,

2006). In comparison, qualitative interview data better illuminate the

way trail organizations manage volunteers, and the relationships

between

management strategies and theoretical best practices. Therefore, the

methodology

for this project consisted of in-depth interviews and event observation

in a case study context. The case study approach entails the

investigation,

development, and analysis of a social unit within the context of a

specific

case (Creswell, 1998; Mitchell, 1983). Inferences from the case

material

are based not upon numerical representativeness, but rather upon

analytical

validity (Mitchell, 1983). Thorough case studies within a social unit

take

place over time through detailed, in-depth data collection involving

multiple

sources of information rich in context (Creswell, 1998).

Our case study was conducted within a non-profit trail-management

organization,

located in the upper Midwest,

during

the spring of 2004. From hereon, the organization (i.e., the social

unit

for this study) will be referred to as the Midwest Trail Society (MTS –

a pseudonym), and the trail which they maintain will be referred to as

the Midwest Trail. The trail runs through seven states, covering

roughly

4,000 miles. The MTS is organized with a national office of eight staff

members, with regional chapters located throughout the seven states.

These

chapters are run by individuals (volunteers themselves) who are tasked

with a variety of responsibilities including event coordination,

fundraising,

landowner relations, advertising, and management of other volunteers.

These

volunteer managers were the subjects of the interviews. The MTS was a

good

fit for this project because they are a local (and easily accessed)

agency

representative of other non-profit trail management organizations

(i.e.,

the Green Mountain Club or the Appalachian Trail Conference).

Fourteen interview participants were identified using a purposeful

sampling

technique. This strategy entails deliberately selecting settings,

persons,

or events for the important information they can provide (Maxwell,

1998;

Patton, 1990). For this study, identification of the participants took

place during discussions with the Director of Trail Management within

the

Midwest Trails Society. In order to develop a more complete

understanding

of the regional nature of the various chapters within the Midwest

Trails

Society, it was decided to contact at least one individual from each of

the seven states through which the Midwest Trail runs. Ten interviews

were

conducted, with four participants abstaining because of time

constraints.

The discussions were semi-structured. While free to explore tangents

and other angles which came about during the course of the discussion,

the discussions focused on a central set of questions. These starting

questions

revolved around the participant’s background with the organization, the

volunteer management framework they were familiar with (if any), their

philosophies regarding volunteers, and examples of volunteer events

which

they had overseen. The discussions lasted between 40 minutes and two

hours

and, with participant consent, were tape recorded and transcribed.

To observe examples of volunteer management in action, one

researcher

attended and participated in four volunteer events organized by the

local

chapter of the Midwest Trails Society. These events encompassed

spring-time

trail construction and maintenance of portions of the Midwest Trail,

and

were advertised on the chapter’s web site. Participation was open to

any

and all interested individuals. Researcher observations were recorded

as

field notes, which allowed the researcher to both corroborate

observations,

made during analysis of the interviews, and determine if the volunteer

events were conducted in a manner consistent with what the managers

were

describing.

To analyze the data, the process of categorical aggregation was

applied

to the interview transcripts and field notes from the volunteer events.

Specifically, categorical aggregation was achieved by the assignment of

a code to facilitate the analysis and review of data. This coding

allowed

the researcher to determine whether or not responses and observations

contained

any elements which could relate to the theoretical ‘best practices’.

Responses

dealing specifically with a best practice were assigned a best practice

code (BP1 to BP7), while other themes were assigned different codes

depending

on the nature of the response. Responses could also be assigned a

combination

of codes. For example, after an interview participant stated “I can’t

give

anybody orders here” in response to a question regarding volunteer

management

strategies, the response was coded “BP4”, in reference to the best

practice

relating to the support function of a manager. Additionally, a code of

“Philosophy” was assigned, as the response indicates some measure of

the

manager’s personal philosophy regarding volunteer management.

Each

interview transcript received two reviews. The first review was

performed

independently by one researcher, with the second being an evaluation of

the first by the other researcher. Coding changes or discrepancies

identified

in the second review were discussed until agreement was reached before

incorporating the data into the final analysis.

In order to carry out this final thematic analysis, an ethnographic

approach was employed to identify major themes. The themes were

identified

by their tendency to emerge from discussion responses, as evidenced by

the coding process. The use of computer software for analysis was

avoided,

as the object of the interviews was to observe underlying themes and

ideas

regarding volunteer management, rather than draw conclusions regarding

the surface meaning of the words themselves (Dutcher et al., 2004).

The information

gathered

from the interview questions was also used to determine if the

modifications

to Ramlall’s framework made sense. This was accomplished by evaluating

the extent to which the best practices help achieve the modified

outcomes

in the context of the MTS. Specifically, the researchers employed a

typological

analysis to establish the relationship of each ‘best practice’ from the

volunteer management literature to a human resource management cluster

within the new framework (Table 1). If the

best

practice could be assigned to a management cluster, it was deemed a

useful

measurement of effectiveness.

The categorical

judgments

relating a best practice to a management cluster resulted from

“convergence

and recurring regularities”

(Henderson, 2006, p. 146)

between the data and the outcomes identified in the revised model. In

other

words, if it was revealed during the interviews that the creation of,

say,

job descriptions helped volunteers make an “effective contribution” to

the organization’s management strategy, then the best practice of job

descriptions

was considered an indicator of the modified outcome. To continue the

example,

the best practice of job descriptions would then be considered to fit

the

framework as an appropriate measure of effectiveness.

Results and Discussion

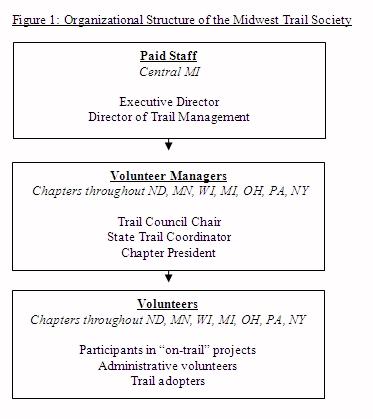

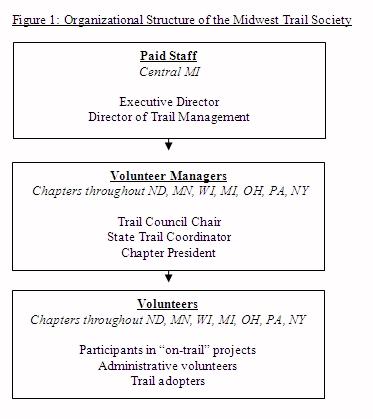

For the purposes

of clarity, a visual representation of the decision-making hierarchy of

the MTS is useful (Figure 1). Throughout this section, the various

levels

of the organization will be referred to as Paid Staff, Volunteer

Managers,

or Volunteers.

Figure

1: Organizational Structure of the Midwest Trail Society

A closer look at the individuals who populate the organization reveals

a wide variety of experiences and history. The Paid Staff, not

surprisingly,

had more previous educational and work experience with environmental

education,

management, and land use than the Volunteer Managers. Specifically,

Paid

Staff reported prior experience in land use planning, land acquisition,

volunteer and partnership support, real estate appraisal, and strategic

planning. The opportunity to apply this experience in a professional

setting

led them to work for the MTS.

Volunteer Managers, on the

other

hand, reported previous experience in a much broader segment of the

workforce,

including the military, tourism, and corporate business environments.

Many

of them reported finding themselves in their current position as

Volunteer

Managers somewhat by accident, beginning with a basic love for hiking

and

the outdoors, and evolving into a gradual acceptance of greater levels

of responsibility. While not quantitatively measured, observation and

discussion

revealed that most Volunteer Managers were over forty years of age and

possessed a college education.

To what extent has the

organization

implemented best practices?

This question was answered using semi-structured, qualitative

interviews

and analysis to investigate the volunteer management strategies of the

Midwest Trail Society. Based upon analysis of these interviews and

accompanying

participant observation, each of the six best practices identified in

the

literature was categorized as either ‘implemented’, or ‘not

implemented’

(Table 2):

Table 2: Summary

of Implementation of Best Practices

|

Implemented

|

Not

Implemented

|

|

|

|

|

1)

Commitment to

volunteer program

|

3)

Job descriptions

|

|

2)

Written policies

|

|

|

4)

Support from manager

to volunteer

|

|

|

5)

Empowerment

|

|

|

6)

Evaluation and

reward

|

|

|

|

|

The evidence

supporting

our finding that best practices 1,2,4,5, and 6 have been implemented by

the MTS is fairly straightforward. For instance, the implementation of

best practice #1, detailing institutional commitment to the volunteer

program,

was revealed in the interviews with the Volunteer Managers:

“I’ve

never had a problem getting help when I’ve called MTS headquarters down

to Lowell.”

“Yes

we’ve had guidelines and support, brochures and that kind of stuff.”

There was universal agreement that the MTS

provides

support in terms of event materials, answering questions, and other

forms

of general support. Since the data revealed a structure of governance

within

the MTS that flows from a board of directors, down to Paid Staff and

Volunteer

Managers, it is evident that this ‘best practice’ was implemented

intentionally.

Additionally, the idea that volunteers need to be developed through

training and teaching (best practice #5) was a strong and clear theme

throughout

the interviews. It was evident throughout the data that the managers

take

this task very seriously:“I think that

the volunteers are the, you know, the number one commodity that any of

these organizations have and that the volunteers really need to be

nurtured

and you know, kind of brought along. You got to kind of gauge people

and

see, you know, what their willingness to be involved is and, you know,

you don’t want to overwhelm people and if you ask too much at the wrong

time, you’ll scare them off.”

Throughout the MTS, it is evident that the Volunteer Managers are

aware

of the importance of nurturing volunteers, and the steps they take to

ensure

empowerment were clear and evident. Furthermore, participant

observation

in trail events revealed that volunteers do indeed become better

workers

as a result of this empowerment.

As the only best

practice

found not to be implemented by the MTS, the creation of job

descriptions

(best practice #3) deserves a closer look. The job description “defines

the role, relationships, responsibilities, obligations, content, power,

and privileges of a volunteer position”

(Heidrich, 1990, p.79).

Job descriptions

can

also be used for recruiting purposes

(Brudney, 1999).

However, recruiting is a challenge for the MTS. In the words of one

Volunteer

Manager:

“It

is something that I think we don’t do a good enough job, frankly, of

attracting

willing workers. That’s one of the things we’d like to improve. I don’t

think the MTS does much better.”

This problem can be

traced to extent to which the MTS provides job descriptions to help

potential

volunteers understand the nature and scope of the work required. At the

chapter level, evidence of comprehensive job descriptions was

inconsistent.

A job description is comprehensive when it specifically describes the

nature

of the position, the scope of work required, and encourages the

volunteer

to get in touch with a chapter representative to find out more. Table 3

provides examples of two types of job descriptions found in one

chapter’s

informational pamphlet:

Table

3:

Sample Job Descriptions

|

Comprehensive

|

|

Incomplete

|

|

|

|

|

|

Work Hikes:

light

brush cutting, trail tread repairs, installing markers and signs

|

|

Trail

Steward: "adopt"

your very own trail section to love and maintain!

|

This inconsistency

was discovered throughout most of the chapters. Interviews with

Volunteer

Managers who coordinated volunteer events and activities revealed that

in most cases, when people expressed an interest in participating, the

leader of the event would simply “lay it out for them” and let people

decide

for themselves which tasks to participate in.

It should be noted,

however, that this practice does not necessarily produce poor results

in

terms of accomplished work. Volunteer Managers felt that oftentimes,

people

were more interested in a day outside and less interested in what was

required

of them. Therefore, they could afford to provide informal job

descriptions.

“Whoever

shows up at a work party, they give a safety lecture at the beginning

and

a person that’s never been there before, they usually tag him on to

somebody

that’s more experienced and say, you know, stay with him today and

he’ll

tell you what to do. Learn by doing.”

Furthermore,

participant

observation revealed that people who arrived at volunteer events did

not

seem to be discouraged by the ambiguity surrounding what was to be

done.

It was observed that people gladly participated in any task which was

asked

as long as it was in line with their physical capabilities.

The various

chapters

of Midwest Trail Society do not have in place a consistent framework

for

providing comprehensive job descriptions. This lack of implementation

does

not seem to be intentional, however. The Director of Trail Management

described

why the MTS has avoided job descriptions:

“The

number of job descriptions has been purposely kept to a minimum and

that

reason being, most of the people that volunteer with Midwest Trail

Society

do a multiplicity of tasks. So while you may be the state board

liaison,

you may also be the chief stamp licker.”

Ultimately,

the lack of comprehensive job descriptions is appropriate for the MTS.

Therefore, even though it is not implemented, this best practice should

remain in our model because it reflects a major difference between

volunteering

and paid employment. This suggests that the modification of Ramlall’s

framework

should incorporate differences between paid and unpaid workers

by, for example, reducing the importance of job descriptions and

increasing

the importance of ensuring volunteer satisfaction with their day on the

trail.

Are the modifications to

Ramlall’s

model relevant in terms of effectiveness?

As noted earlier, each of Ramlall’s seven human resource management

clusters and their outcomes can be modified to transition the model

from

a corporate, business standpoint to a non-profit, volunteer, trail

management

perspective (Table 1). To determine the relevance of such

modifications,

each best practice from the volunteer management literature was

compared

to a human resource management cluster within the modified framework.

If

the best practice could be assigned to a management cluster, it

demonstrated

that the practice helped achieve the modified outcomes. If this

relationship

could not be determined, then the modifications were deemed irrelevant.

Best Practice One: The best practice of securing commitment

to

a volunteer program from higher levels helped achieve the outcomes

associated

with the Strategic Planning (#1) and Organizational

Behavior

and Theory

(#7) clusters in the adapted model (Table 1). Specifically, securing

commitment

from higher levels of the organization is in tune with a strategic

planning

outcome that necessitates “analys[e]s, decisions, and actions needed to

create and sustain” a functional volunteer program (Ramlall, 2003,

p.61).

In terms of the MTS, the data revealed that support and commitment

from

the Paid Staff in Lowell

helps Volunteer Managers ensure that their programs will be consistent

with established organizational cultures and strategies. A good example

of how this support enhances the strategic planning initiatives of the

organization involves the development of a workshop to assist Volunteer

Managers with land issues:

“We are

tailoring a workshop. It is going to be called, Land and Trails

Workshop.

In that workshop, the first in a series, it is going to take place in

New

York, then move down to Pennsylvania, then come to western Michigan and

we’ll go around the seven states, like a road show. It will be kind of

onsite two-day training and when they walk out of there, they will be

fully

trained on the various aspects of land negotiations and conservation

easements

and all of that kind of fun real estate stuff and legal stuff and they

will also walk out of there with a handbook at the end of the training

and a badge.”

Best Practice Two: The best practice of having formal, written

procedures to govern the operation of a volunteer program helped

achieve

the outcomes associated with the

Strategic Planning (#1) and Performance

Management

(#5) clusters within the adapted model (Table 1). Written policies and

procedures are one example of the “integration in all areas of the

organization”

that is a trademark of successful strategic planning (Ramlall, 2003,

p.61).

Additionally, written policies and procedures available to a manager

can

aid performance management by facilitating the development of processes

which maximizing performance (Ramlall, 2003).

The interviews further suggest that written procedures will enhance

planning and management within the organization, because they can

create

consistency among chapters in regards to volunteer management policy.

For

example, the MTS provides Volunteer Managers with a publication to

ensure

consistent fundraising practices, regardless of the experience of the

volunteer:

“We

have additional resources that are available through the Lowell

headquarters and the thing that comes to mind right now was a

publication

that we circulated and put out that was called, you know, Easy Money.

And

this was 101 ways, so-to-speak, of how to raise funds and how to

organize

people to raise funds at the chapter level. And it is generic in that

it

is something that could be given to the lowliest of brand new

volunteers.

It could also be given to one of our more sophisticated presidents or

treasurers

and at the same time, is not exclusive to a chapter, but rather could

be

used by a state council to do pretty much the same thing.”

If every chapter is familiar and comfortable with the formal

procedures,

the resulting consistency can foster long-term strategic planning and

ensure

that the work being carried out supports the mission of the MTS.

Best Practice Three: The best practice of creating

comprehensive

job descriptions was an important element in achieving the outcomes

associated

with the Acquisition of Employees

(#2) cluster (Table 1). Job descriptions which clearly lay out the

responsibilities

of the volunteer position will ensure not only the volunteer’s

happiness,

but will also contribute to reduced volunteer turnover, a larger pool

of

volunteers, and higher levels of performance from those volunteers

(Ramlall,

2003).

In the case of the MTS, however, it was not worthwhile to implement

job descriptions beyond those already in place for short-term projects

and work trips. Many managers indicated that volunteers “just want to

spend

a day on the trail” and “don’t really care what they do” and are

already

familiar with the type of work that is performed during a project or

work

outing. When new volunteers arrive who are unfamiliar with the nature

of

the work, the managers felt any confusion could be overcome by spending

time with the volunteer or closely observing their work. Participant

observation

revealed that the volunteers shared this sentiment, as first-time

volunteers

were observed to be willing to tackle any necessary task, as long as it

was consistent with their physical abilities.

Best Practice Four: The best practice of providing support to

volunteers achieves the outcomes associated with the Training and

Development

(#3), Organizational Change and Development (#4), and Organizational

Behavior and Theory

(#7) clusters in the modified model (Table 1). Support, in this case,

can

consist of an orientation to the organizational culture, or logistical

support such as directions to events.

Providing support to volunteers is a perfect example of a Training

and

Development approach involving

“support from peers, supervisors and others”,

which may affect the attitude of participants (Ramlall, 2003, p.61). In

terms of Organizational Change and Development, the support provided by

managers can ensure the enhanced productivity and quality that the

organization

seeks (Ramlall, 2003). Finally, support from manager to volunteer can

help

the organization achieve consistency in terms of culture and strategy,

which is the primary outcome of the Organizational Behavior and Theory

cluster (Ramlall, 2003).

In terms of the MTS, this best practice is a useful tool because not

only are chapter managers the primary means of keeping the volunteer

program

functioning, but also their support enhances worker productivity along

the trail. In addition, the support of managers maintains the

organization.

As one manager stated, “it is surprising how much you can accomplish

that

way with retaining membership and getting people interested.”

Best Practice Five: The best practice of empowering

volunteers

through teaching and training achieves the outcomes associated with the

Training

and Development

(#3) cluster (Table 1) (Ramlall, 2003). The process of nurturing

volunteers

will contribute to a “positive change in attitude”, “increased

expertise”,

and enhanced “opportunities to practice newly acquired skills on the

job”

(Ramlall, 2003, p.61).

In the case of the MTS, this

best practice is essential, since, as several managers stated, “without

volunteers there is no trail”. Assuring that volunteers are empowered

through

education and training improves not only the performance of the

individual,

but the processes of trail maintenance and the health of the

organization

as well

(Ramlall, 2003).

On the other hand, Volunteer

Managers were concerned with a significant pitfall inherent to

empowering

volunteers:

“It’s

called

the 80/20 rule. 20 percent of the people do 80 percent of the work. In

any organization you tend to find that a small number of people, the

cadre

does most of the work, the planning and the execution.”

In

addition to the care that must be taken to ensure that a select few are

not being saddled with a disproportionate share of the work, managers

need

to be aware of changing volunteer expectations that result from

empowerment.

Psychological contracts, which are “informal, unwritten, mutually

independent

sets of expectations” (Propst et al., 2004, p.397) between volunteers

and

organizations, are often violated as managers are not always aware of

volunteer

expectations (Propst & Bentley, 2000).

Best Practice Six: The best practice of implementing a system

of observation, evaluation, and praise was determined to achieve the

outcomes

within the Reward System (#6) and Performance Management

(#5) clusters (Table 1). Having in place a reward system for volunteers

is the primary method for “motivat[ing] increased performance”

(Ramlall,

2003, p.61). Furthermore, observation and evaluation can be an

“effective

process for maximizing performance” (Ramlall, 2003, p.61). It should be

noted that in this context, evaluation refers to the

evaluation

of the work performed by the volunteer and not a global evaluation of

the

overall volunteer program, which would use a different metric such as

the

number of hours worked or the miles of trail built by volunteers.

For the MTS, the reasons for having a system in place to reward

volunteers

is obvious, since, as one manager stated, “none of it would be possible

without the volunteers.”It

is important to note, however, that care must be taken during the

evaluation

process because the feedback sometimes “carries connotations of ‘being

judged’ and seems to question the volunteer’s ‘gift’ or donation of

time”

(Brudney, 1999, p239). The managers are aware of this, however. As one

noted, “Obviously, you don’t go out and beat ‘em over the head. You are

not going to have too many people if you do that.” Additionally, there

is some question regarding how much reward volunteers are actually

looking

for in cases where the volunteers consider their work to be a civic

duty

(Propst, et al., 2004).

The synergy between the goals of the MTS, and the outcomes of the

adapted

model, initially revealed that the modifications were appropriate.

Analysis

of the data gathered through interviews and participant observation

demonstrated

that the MTS has purposefully implemented management strategies

specifically

designed to maximize the impact of its volunteer workforce, and that

those

strategies achieved outcomes similar to those in the modified model

(Table

1). Thus, assessing the outcomes of the modified model in Table 1 is an

appropriate way to measure effectiveness. Had the data shown that the

management

strategies of the MTS focused on non-volunteer areas, such as employee

relations, government regulations, or customer service, the

modifications

to Ramlall’s model would not have been appropriate.

Conclusions

Many of the organizations involved with the management of recreation

trails would not exist without the work of volunteers. Therefore,

having

some sort of carefully considered framework in place to see that their

work is efficiently and effectively managed is crucial. This analysis

has

shown that best practices can serve as that framework. First,

implementation

of best practices can help a trail management organization better

manage

its volunteer workforces. The Midwest Trail Society, through the work

of

dedicated individuals at the chapter and national level, has adopted

and

implemented five of the six best practices for managing volunteers as

recommended

in the literature. It was clear through interviews with enthusiastic

managers

and observation of smoothly-run volunteer events that the use of these

best practices is helping the MTS achieve its mission – the maintenance

and protection of the Midwest Trail.

Additionally, the

role

of best practices can be broadened to include their use as tools to

achieve

effectiveness outcomes. This research has shown that an existing model

designed to measure the effectiveness of human resource management in a

business context can be modified to measure the effectiveness of

volunteer

management in a non-profit context. Specifically, Ramlall’s management

clusters and their associated outcomes were modified to transition his

model from a business-based standpoint to a non-profit, volunteer,

trail

management perspective. These modifications included the removal of

outcomes

associated with hiring, customer service, and financial remuneration

and

instead adapting? terminology to better reflect the volunteer function.

Since the best practices outlined by the literature helped achieve the

outcomes of each modified cluster, the modification to Ramlall’s model

was appropriate (Table 4).

Table 4: Relationship of Best

Practices

to Ramlall’s Management Clusters

|

Management Cluster

|

Modified Volunteer

Outcome

|

Volunteer Best

Practice

|

|

|

|

|

1.

Strategic Planning

|

a)

Analysis, decisions,

and actions needed to create and sustain a functional volunteer program

|

1) Commit

to volunteer

program 2) Provide written policies to

govern

the program

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.

Acquisition of

Employees

|

a)

“Effective contribution”

of new volunteers, b) “Planning process, advertising, and recruitment

sources”

should fit the organization’s management strategy

|

3) Create

job descriptions

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. Training

&

Development

|

a)

Increased expertise in areas applicable to job, b) Opportunities to

practice

newly acquired skills on the job, c) Support from peers, supervisors,

and

others in using knowledge gained

|

4) Provide

support

activities 5) Empowerment

|

|

|

|

|

|

4.

Organizational

Change & Development

|

a) Higher

levels

of productivity, b) quality of work performed, c) fluid organizational

structures

|

4) Provide

support

activities

|

|

|

|

|

|

5.

Performance Management

|

a) Each

volunteer

“position and task supports strategic objectives, b) Effective process

for maximizing performance

|

2) Provide

written

policies to govern the program

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. Reward

System

|

a) Reward

system

motivates increased performance

|

6)

Evaluation of

work performed

|

|

|

|

|

|

7.

Organization Behavior

& Theory

|

a)

Behaviors reflect

desired organizational culture and alignment with organizational

strategy

|

1) Commit

to volunteer

program 4) Provide support activities 6) Evaluation of work performed

|

The fact that this modified model aligned so

well with the MTS effectiveness strategies indicates that it may also

be

appropriate for other recreation organizations that rely on substantial

volunteer input.

The data revealed that the MTS had not implemented the best practice

involving job descriptions. While a lack of specific job descriptions

may

pose problems (in terms of efficiency or legality) for other types of

volunteer

organizations, the MTS had organization-specific reasons why job

descriptions

were not put into practice. This indicates that managers of volunteers

in organizations like the MTS should hand-craft any implementation of

best

practices to fit their specific situation. They can accomplish this

through

formalization and periodic evaluation of policy within a larger

framework

designed to measure the effectiveness of the volunteer program. For

example,

the MTS is continually evaluating the status of its volunteer

workforce,

using software tools such as Donor Soft to catalogue activity and

measure

trends, giving it the power to adjust volunteer management strategies

accordingly.This

research does not intend to present the literature-driven theoretical

best

practices as all-inclusive. For example, organizations could consider

alternative

best practices such as the solicitation of feedback from volunteers, or

the construction of a formal budget to manage the volunteer program

(Brudney,

1999). Furthermore, the act of ensuring communication between different

levels of the organization could be a best practice, along with

understanding

the motivations of the volunteers themselves. Managers who are tasked

with

caring for a volunteer workforce should be encouraged to seek out new

ideas,

test new concepts, and develop their own best practices. Each

organization

is faced with its own specific situation and its own set of challenges,

and only through continued experimentation and research can the concept

of best practices be applied to as many different situations as

possible.

Additional research in this area should increase the focus on small,

non-profit trail management organizations. These groups accomplish much

with very little, and the stories, backgrounds, and histories of their

members are fascinating. The recreation, natural resource and nonprofit

management professions have much to learn from these dynamic

organizations.

References

Appalachian

Mountain Club (Ed.). (2003). AMC White Mountain Guide, 27th

Edition. Boston, MA: AMC Books.

Appalachian

Trail Club. (2005). A.T.thru-hiking facts and statistics. Referenced

February

11, 2005 from www.appalachiantrail.org/hike/thru_hike/facts.html.

Arai,

S. M., & Pedlar, A. M. (1997). Building communities through

leisure:

Citizen participation in a healthy communities initiative. Journal

of

Leisure Research, 29(2), 69-81.

Barnett,

M. L. (2002). A zen approach to volunteer management. The Journal

of

Volunteer Administration, 20(3), 41-47.

Bradner,

J. H. (1993). Passionate volunteerism. Winnetka, IL:

Conversation

Press, Inc.

Brudney,

J. L. (1999). The effective use of volunteers: Best practices for the

public

sector. Law and Contemporary Problems, 62(4), 219-255.

Campion

Devney, D. (1992). The volunteer's survival manual. Cambridge,

MA:

The Practical Press.

Clarke,

J., & McCool, D. C. (1996). Staking out the terrain: Power and

performance

among natural resource agencies. Albany, NY: State University of

New

York Press.

Clary,

G. E., Snyder, M., & Ridge, R. (1992). Volunteer motivations: A

functional

strategy for the recruitment, placement, and retention of volunteers. Nonprofit

Management & Leadership, 2(4), 333-350.

Creswell,

J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing

among

five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cuskelly,

G., Hoye, R., & Auld, C. (2006). Working with Volunteers in

Sport:

Theory and Practice. London: Routledge

Dutcher,

D., Finley, J., Luloff, A. E., & Johnson, J. (2004). Landowner

perceptions

of protecting and establishing riparian forests: A qualitative

analysis.

Society

and Natural Resources, 17(4), 319-322.

Ellis,

S. (1996). From the Top Down: The Executive Role in Volunteer

Program

Success. Philadelphia, PA: Energize, Inc.

Farmer,

S. M., & Fedor, D. B. (1999). Volunteer participation and

withdrawal:

A psychological contract perspective on the role of expectations and

organizational

support. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 9(4), 349-367.

Forsyth,

J. (1999). Volunteer management strategies: Balancing risk and reward.

Nonprofit

World, 17(3), 40.

Govekar,

P., & Govekar, M. (2002). Using economic theory and research to

better

understand volunteer behavior. Nonprofit Management &

Leadership,

13(1), 33-48.

Gratton,

L., & Ghoshal, S. (2003). Managing personal human capital: A new

ethos

for the 'volunteer' employee. European Management Journal, 21(1),

1-10.

Green

Mountain Club. (2005) Frequently asked questions. Retrieved February

11,

2005 from www.greenmountainclub.org/faq.htm.

Grese,

R. E., Kaplan, R., Ryan, R. L., & Buxton, J. (2000). Psychological

benefits of volunteering in stewardship programs. In R. B. Hull (Ed.),

Restoring

nature: perspectives from the social sciences and humanities (pp.

265-280).

Washington, DC: Island Press.

Grossman,

J. B., & Furano, K. (1999). Making the most of volunteers. Law

and

Contemporary Problems, 62(4), 199-218.

Hardy,

D., Larose, S., & Rose, B. (Eds). (2003). Long Trail Guide

(25th

ed.). Waterbury, VT: The Green Mountain Club.

Heidrich,

K. W. (1990). Working with volunteers in employee services and

recreation

programs. Champaign, IL: Sagamore Publishing, Inc.

Henderson,

K. A. (2006). Dimensions of choice: A qualitative approach to

recreation,

parks, and leisure research, 2nd Edition.. State

College,

PA: Venture Publishing, Inc.

Independent

Sector. (2005). Giving and volunteering in the United States.

Retrieved

September 2, 2005 from From www.independentsector.org/.

Jackson,

D. (2003). Volunteers in natural resource, outdoor recreation, and

environmental

management and planning: Understanding the role of expectations in the

fulfillment of psychological contracts. Unpublished M.S., Michigan

State University, East Lansing, Michigan.

Lee,

J. F., & Catagnus, J. M. (1999). What we learned (the hard way)

about supervising volunteers. Philadelphia, PA: Energize, Inc.

Liao-Troth,

M. A. (2001). Attitude differences between paid workers and volunteers.

Nonprofit

Management & Leadership, 11(4), 423-442.

Maxwell,

J. A. (1998). Designing a qualitative study. In D. J. Rog (Ed.), Handbook

of applied social research methods (pp. 69-100). Thousand Oaks, CA:

Sage Publications.

McCurley,

S., & Lynch, R. (1996). Volunteer management - Mobilizing all

the

resources in the community. Downers Grove, IL: Heritage Arts

Publishing.

McDonough,

M., & Wheeler, C. W. (1998).

Toward school and community collaboration

in social forestry: Lessons from the Thai experience. Washington,

D.C.:

U.S. Agency for International Development.

Mitchell,

J. C. (1983). Case and situation analysis. The Sociological Review,

31, 187-211.

Patton,

M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods.

Newbury

Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Payton,

M., Fulton, D., & Anderson, D. (2005). Influence of place

attachment

on civic action: A study at Sherburne National Wildlife Refuge. Society

and Natural Resources, 18(6), 511-528.

Pharoah,

C. (Ed.). (1997). Dimensions of the voluntary sector: Charities

Aid Foundation.

Propst,

D. B., & Bentley, S. C. (2000).

Trends in citizen participation

in outdoor recreation and resource management: Manager vs. citizen

perspectives.

Paper presented at the Fifth Outdoor Recreation and Tourism Trends

Symposium,

East Lansing, MI.

Propst,

D. B., Jackson, D., & McDonough, M. (2004). Public participation,

volunteerism

and resource-based recreation management in the U.S.: What do citizens

expect? Society and Leisure, 26(2), 389-415.

Ramlall,

S. J. (2003). Measuring human resource management's effectiveness in

improving

performance. Human Resource Planning, 26(1), 51-62.

Schroeder,

H. W. (2000). The restoration experience: Volunteer's motives, values,

and concepts of nature. In R. B. Hull (Ed.), Restoring Nature.

Washington,

DC: Island Press.

Smith,

P., & McDonough, M. (2001). Beyond public participation: Fairness

in

natural resource decision making. Society and Natural Resources, 14,

239-249.

Stebbins,

R. A. (1992). Amateurs, professionals, and serious leisure.

London:

McGill-Queen's University Press.

Stebbins,

R. A., & Graham, M. (Eds.). (2004). Volunteering as Leisure: An

International Assessment. London: CABI Publishing.

U.S.

Department of Labor Statistics (2005).

Volunteering in the United States,

2004. Retrieved September 4, 2005 from

www.bls.gov/news.release/volun.nr0.htm.

Wilson,

M. (1978). Effective management of volunteer programs. Boulder,

CO: Volunteer Management Associates.

Wilson,

A., & Pimm, G. (1996). The tyranny of the volunteer: The care and

feeding

of voluntary workforces. Management Decision, 34(4), 24-41.