Comparative Analyses of Constraint Negotiation Strategies

in Campus Recreational Sports

Daniel J. Elkins, Ph.D.

Daniel J. Elkins

School

McCormick Hall 100A - Campus

Normal

Phone: (309) 438-5383

Email:

Brent A. Beggs

Assistant Professor

Illinois

School

McCormick Hall 211 - Campus

Normal

Phone: (309) 438-5753

Email:babeggs@ilstu.edu

Negotiation strategies were compared based on level of participation and perceived level of constraint using 2 X 2 Analysis of Variance (ANOVA).Results indicated significant differences in negotiation between regular participants in campus recreational sports and those who did not participate regularly in the use of time management, physical fitness, interpersonal coordination, and improving finances strategies.Significant differences in negotiation were also found among students with differing levels of perceived constraint in utilization of negotiation strategies.The higher the perception of structural constraints, the more likely an individual was to make attempts to modify their schedule and make financial adjustments in order to make time to participate.Additionally, individuals moderately constrained were significantly more likely to use change their leisure aspirations than those who perceived a low level of intrapersonal constraint.

The

results of this study indicate that an individual’s willingness to

negotiate

leisure constraints plays an important role in participation in campus

recreational sports.By addressing different

constraints

and negotiation strategies, campus recreational sports providers may be

able to meet the needs of more students and increase levels of

participation.

<>Crawford and Godbey (1987) categorized three types of constraints in defining the fundamental differences in constraining factors.Structural constraints include such factors as the lack of opportunities or the cost of activities that result from the external conditions in the environment (Mannell & Kleiber, 1997), such as a lack of time or a lack of money to participate.Interpersonal constraints arise from the interactions with other people, or the concept of interpersonal relations in general.Interpersonal constraints may be experienced if an individual is unable to locate a partner with whom to participate in a specific leisure activity.Finally, intrapersonal constraints refer to psychological conditions that arise internal to the individual such as personality factors, attitudes, or more temporary psychological states such as moods.Though a great deal of research has examined constraints to participation in leisure activities, very little research has contributed to a universal understanding of how constraints affect those that overcome constraints and enable them to engage in leisure.

The concept of constraints as “negotiable” emerged in the early 1990s, extending the discussion of constraints and how they limit participation and also how leisure is incorporated into everyday lives (Henderson & Bialeschki, 1993; Little, 2000; Samdahl & Jekubovich, 1997).According to Crawford, Jackson, and Godbey (1991), leisure participation is heavily dependent on negotiating through an alignment of multiple factors, arranged sequentially, that must be overcome to maintain an individual’s impetus through these systematic levels.Essentially, one must negotiate constraints in order to increase the likelihood of meaningful participation and have the opportunity for a leisure experience.

Jackson

In a study conducted in a corporate recreation setting, Hubbard and Mannell (2001) used the strategies developed by

Several studies have examined perceived constraints of participants engaging in sport-related activities, including Young, Ross, and

Sections A and B of the instrument were comprised of demographic information, participation frequencies, and participation preferences relative to recreational sports programs.Section C included 25 items used to measure perceived constraints.These items are based on an instrument used in a study by Young, Ross, and

Individual mean responses to structural, intrapersonal, and interpersonal items were used to establish the level of perceived constraint for the purpose of determining if significant differences existed among these levels in terms of the negotiation of constraints.Categorization of each type of constraint on two levels (low and moderate) enabled mean score comparisons of negotiation strategies at each level of structural, intrapersonal, and interpersonal constraint.The perceived level of constraint used to make these comparisons was dependent upon the nature of the negotiation strategy.The use of a time management strategy, for example, implies the need to modify one’s schedule in order to make time to participate.The use of a time management strategy may logically follow the perception of a structural constraint, such as a lack of time.

Section D of the instrument included 30 negotiation strategies developed by

Differences in negotiation based on these responses were examined based on level of participation and perceived level of constraint.Specifically, comparisons of those that participated in campus recreational sports were conducted with those that were not regular participants for each of the negotiation strategy categories, as well as the levels of perceived constraint formed based on responses to Section C of the instrument.2 X 2 Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was conducted for each negotiation strategy category.A Bonferroni adjustment was utilized to correct for multiple comparisons (p?0.0016).In addition, a comparison of responses between the two universities was indicated no significant differences in any of the items.

Results

The total number of

respondents

in the study was 955.Listwise deletion of 44

respondents

who failed to properly complete the questionnaire was implemented

reducing

the response rate to 35.48% (N=911).Of the 911

respondents,

only 36.21% considered themselves to be regular participants in campus

recreational sports programs. Regular participation was defined as

participation

at least once per week.An assessment of the

degree

to which the sample perceived constraints shows that, overall, students

who participated in this study were minimally constrained with regards

to participation in campus recreational sports (M=2.28).Responses

indicated that the most constraining factors were “lack of time because

of work, school, or family” (M=3.93), “facilities are too crowded”

(M=3.04),

and “lack of time because of other leisure activities” (M=2.87), all of

which were structural in nature.Students

perceived

mostly structural constraints (M=2.65), followed by interpersonal

(M=2.11)

and were least affected by intrapersonal constraints (M=1.83).In

addition, both participants and non-participants in campus recreational

sports perceived mostly structural constraints, followed by

interpersonal,

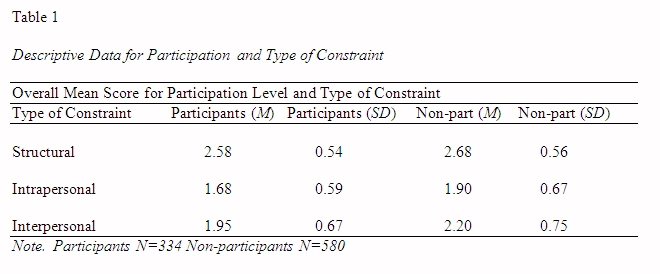

and intrapersonal (Table 1).

Two categories of perceived constraint were utilized in comparing negotiation strategies.A low level of perceived constraint (mean score of 3 or less) and a moderate level of perceived constraint (mean greater than 3) were established to define the degree to which an individual perceived structural, interpersonal, and intrapersonal constraints.As a result of this grouping strategy, a total of 647 students perceived a low level of structural constraint, while 264 perceived a moderate level. Interpersonally, 764 students perceived a low level of constraint while only 147 perceived a moderate level.Students considered themselves to be least affected by intrapersonal constraints, as only 54 students were categorized as moderately constrained.

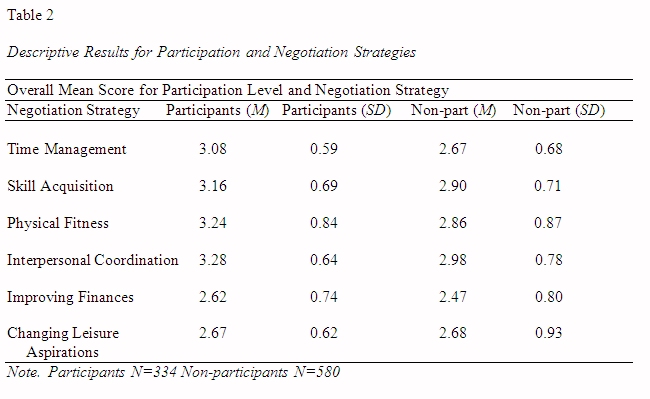

The specific negotiation strategies most utilized by students were “I try to get better organized,” (M=3.48), “I encourage friends to participate with me” (M=3.45), and “I am willing to participate with people I don’t know” (M=3.39).Students most utilized interpersonal coordination strategies (M=3.08) followed by skill acquisition (M=2.99), physical fitness (M=2.99), time management (M=2.82), and changing leisure aspirations (M=2.68).Students who participated in this study least utilized improving finances strategies (M=2.52).

Negotiation and level of

participation

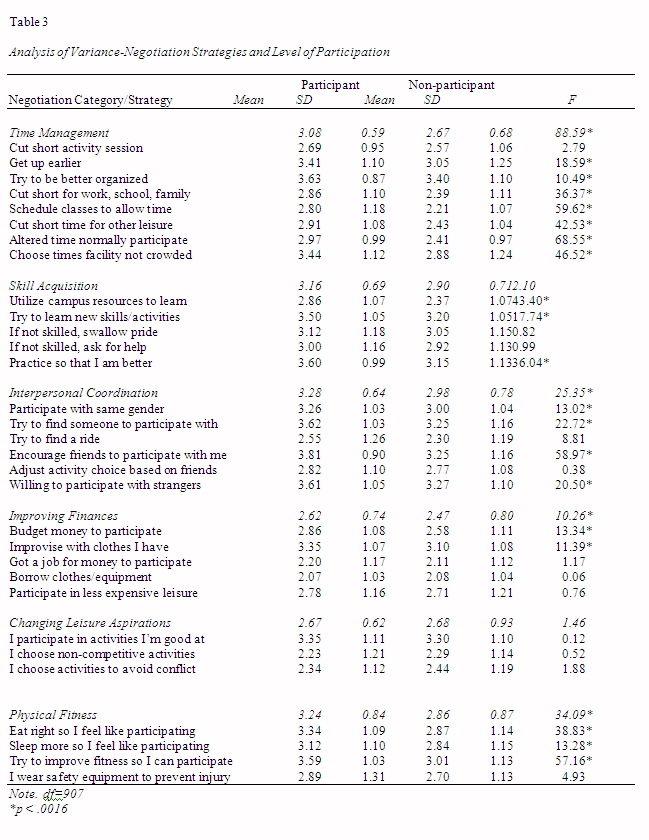

Results indicated significant differences in four of the six negotiation categories between regular participants in campus recreational sports and those who did not participate regularly (Table 3).Regular participants were significantly more likely to use time management negotiation strategies (p?0.001) such as shortening an activity session, physical fitness strategies (p?0.001), such as getting more sleep, interpersonal coordination strategies (p?0.001), such as attempting to find someone with whom to participate, and improving finances strategies (p?0.001), such as budgeting money in order to afford participation, or improvising activity choices.There were no significant differences in the use of skill acquisition or changing leisure aspiration strategies among regular participants and those that did not participate on a regular basis.Differences in the use of specific negotiation strategies are summarized in Table 3.

<>

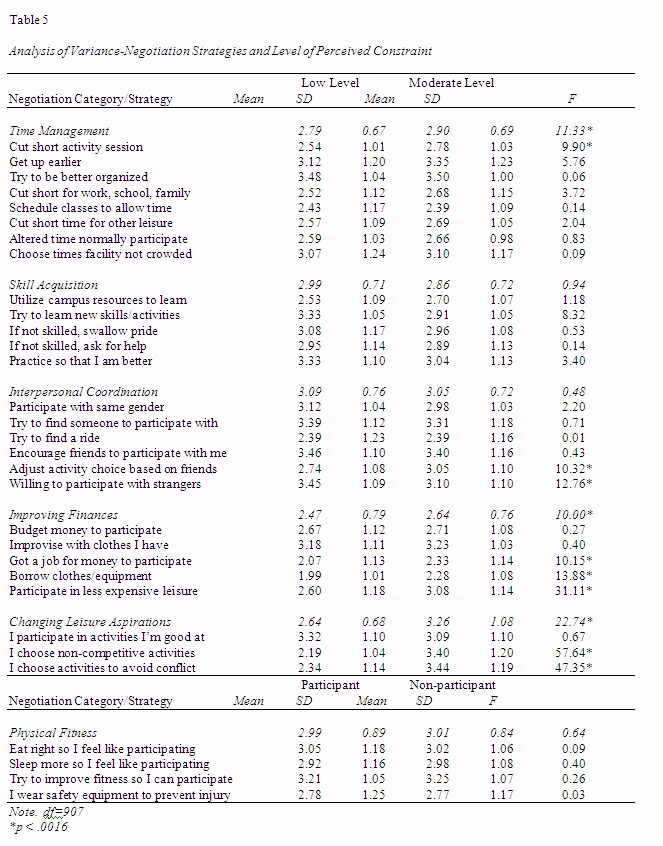

<>Negotiation and perceived level of constraint

<>

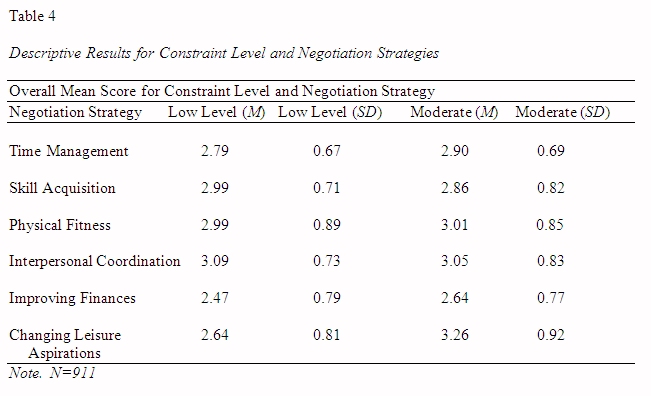

Those categorized as moderately constrained most often reported the use of changing leisure aspirations strategies (M=3.26), followed by interpersonal coordination (M=3.05), physical fitness (M=3.01), time management (M=2.90), skill acquisition (M=2.86), and least utilized improving finances strategies (M=2.64).Means for those who perceived a lower level of constraint indicated less use of time management, physical fitness, improving finances, and changing leisure aspirations, and greater use of interpersonal coordination and skill acquisition negotiation strategies (Table 4).

<>

Further analyses were conducted to determine if there was a statistical difference in negotiation among low and moderately constrained students.

Moderately constrained college students were significantly more likely to utilize negotiation strategies in three of the six negotiation categories (Table 5).Those who perceived a moderate level of structural constraint were significantly more likely to utilize time management (p?0.001) and improving finances strategies (p?0.001), while those who perceived a moderate level of intrapersonal constraint were significantly more likely to utilize changing leisure aspirations negotiation strategies (p?0.001).There was not a significant difference in means between students in the two categories in terms of their use of physical fitness, skill acquisition, and interpersonal coordination strategies.Differences in the use of specific negotiation strategies are summarized in Table 5.

With regards to time management negotiation, a significant interaction effect resulted between the structural level of constraint and level of participation (p=.024).As a result, additional analyses were conducted to further understand the differences among the two independent variables.Results from this analysis indicated that participants at the low level of structural constraint (M=3.01) differed significantly from non-participants at the low level of structural constraint (M=2.65) in terms of time management negotiation strategies.Additionally, significant differences were also discovered among the participants moderately constrained (M=3.29) and non-participants moderately constrained (M=2.71).

Discussion

Though not the primary focus

of this study, leisure constraints were nonetheless an important aspect.College

students who participated in the study indicated that the lack of time

because of work, school, or family was the most constraining factor

(M=3.93).This

supports research findings by Young, Ross, and

Few studies that have examined leisure constraints or negotiation strategies have collected data from non-participants.It was important for this study to determine constraining factors to the non-participants as well as the difference in negotiation as it related to individual participation in campus recreational sports programs.Results showed significant differences in negotiation between those who participated regularly and those who did not in how they used time management, physical fitness, interpersonal coordination, and improving finances strategies.

Time management comparisons indicated that participants were significantly more likely to use time management strategies than non-participants.This finding suggests that negotiation had a significant and positive impact on the frequency of participation in campus recreational sports.The same can be stated for strategies of interpersonal coordination, physical fitness, and improving finances.In a separate analysis, participants were significantly more likely to negotiate constraints than non-participants.Those who participated in campus recreational sports once per week were more willing to find a way to participate than those who did not.This may indicate a commitment to participating in campus recreational sports programs.This level of commitment may be linked to an individual’s level of motivation to participate as suggested by Jackson, Crawford, and Godbey (1993) and Alexandris, Tsorbatzoudis, and Grouios (2002).

Significant differences in negotiation were found among students with a low perceived level of constraint and those moderately constrained in how they used negotiation strategies.The higher the perception of structural constraints, the more likely an individual was to make attempts to modify his/her schedule and make financial adjustments in order to make time to participate.Additionally, individuals moderately constrained were significantly more likely to change leisure aspirations, such as the avoidance of overly competitive activities, than those who perceived a low level of intrapersonal constraint.These results support research findings by Hubbard and Mannell (2001), who found that when an individual perceived an increase in constraint, they were more likely to attempt to overcome the constraint using negotiation.

A significant interaction among level of participation and level of perceived structural constraints suggests that participants moderately constrained were significantly more likely to use time management negotiation strategies than participants with lower levels of structural constraints.The specific difference in negotiation among participants with low and moderate levels of constraint was expected as participants who encounter a high level of constraint would need to negotiate more to maintain regular participation in campus recreational sports.

<>

It could also be concluded that those who perceived a low level of constraint utilized fewer negotiation resources simply because they did not perceive constraining factors.Individuals who had an increased perception of the constraint would naturally have to negotiate more frequently in order to participate.Alternatively, a moderately constrained campus recreational sports participant could be more motivated to participate, resulting in an increased likelihood of negotiating the constraint.Additional research is needed in this area in order to determine if there is a level of constraint that significantly reduces the likelihood of campus recreational sports participation.Furthermore, research examining the role that motivation plays in the negotiation process could assist in understanding the difference between the failure to negotiate and the lack of interest or awareness of the programs.

College students perceive constraints on multiple levels when considering participation in campus recreational sports and leisure activities in general.However, findings from this study suggest that if a student is able to overcome or negotiate those constraints, then they are more likely to participate in recreational activities.It is the responsibility of campus recreational sports providers to consider constraint and negotiation issues in planning recreational activities.Traditionally, campus recreational sports providers have been successful in scheduling activities at appropriate times and keeping fees to a minimum.Future activity planning should also consider providing social experiences and skill development in campus recreational sports programming.By addressing these needs, college students may be more likely to participate in campus recreational sports.

References

317-332.

Alexandris, K., Tsorbatzoudis, C., & Grouios, G. (2002).Perceived

constraints on recreational sport participation: Investigating their

relationship

with intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and

amotivation. Journal

Leisure Research, 34(3), 317-332.

Alfadhil, A. M. (1996).University students’

perception of constraints to participation in recreational sports

activities.Dissertation Abstracts

International,

57 (09), 4127A.(UMI No. 9706441).

Buchanan, T., & Allen, L. (1985).Barrier

to

recreation participation in later life cycle stages.

Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 19, 39-50.

Crawford, D. W., & Godbey, G. (1987).Reconceptualizing

barriers to family leisure.

Leisure Sciences, 9, 119-127.

Crawford, D. W.,

Dillman, D. A. (2000).Mail and internet

surveys:The

tailored design method.New York, NY:John

Wiley & Sons.

Henderson

Hubbard, J., & Mannell, R. C. (2001).Testing

competing models of the leisure constraint negotiation process in a

corporate

employee recreation setting.Leisure Sciences,

23, 145-163.

Jackson, E. L., Crawford, D. W., & Godbey,

G. (1993).Negotiation of leisure constraints.Leisure

Sciences, 15, 1-11.

Jackson, E. L., & Rucks, V. C. (1995).Negotitation

of leisure constraints by junior-high and high-school students:An

exploratory study.Journal of Leisure Research,

27, 85-105.

Samdahl, D. M., &

Scott, D. (1991).The problematic nature of

participation

in contract bridge:A qualitative study of

group-related

constraints.Leisure Sciences, 13, 321-336.

Mannell, R. C., & Kleiber, D. A. (1997).A social psychology of leisure.Venture Publishing: State College, PA.

Young, S. J., Ross, C. M., &